Black History Month: Reflecting on Teaching & Learning

ED TECH SPOTLIGHT

quote Heading link

Education was a revolutionary process that provided a counter-narrative to enslavement and subjugation, and centered [the] experiences and contributions [of enslaved Africans] in the telling of the American story.

TEXT Heading link

As we take the time to learn, acknowledge, and reflect on Black History this month, it is important to center African Diasporic pedagogical practices as a precursor to antiracist and inclusive teaching strategies. As early as the 1740’s, Southern legislatures enacted laws restricting the education of enslaved Africans, which increased in severity through the Civil War.[1] In 1818, the city of Savannah, Georgia passed a city ordinance “by which any person that teaches any person of color, slave or free, to read or write or causes such persons to be so taught, is subjected to a fine of thirty dollars for each offense; and every person of color who shall keep a school to teach reading or writing is subject to a fine of thirty dollars, or to be imprisoned ten days, and whipped thirty-nine lashes.” [2] In 1831, the North Carolina legislature made teaching enslaved Africans to read or write punishable “with thirty-nine lashes, or imprisonment, if the offender be a free negro; but if a white, then with a fine of $200 [because] teaching slaves to read and write tends to dissatisfaction in their minds, and to produce insurrection and rebellion.”[3] Patrols were also ordered in the State to “search every negro house for books or prints of any kind [including Bibles] and hymn books].”[4] Perhaps the most draconian anti-literacy laws were found in Louisiana, where

- any person using language in any public discourse, from the bar, bench, stage, or pulpit, or in any other place, or in any private conversation, or making use of any signs or actions having a tendency to produce discontent among the free colored population, or insubordination among the slaves, or who shall be knowingly instrumental in bringing into the State any paper, book, or pamphlet , having the like tendency, shall, on conviction, be punished with imprisonment or death, at the discretion of the Court.[5]

The rationale for these laws was that educating enslaved Africans was inconsistent with their status as chattel. They were not “regarded as a [members] of society, nor as human [beings].”[6]

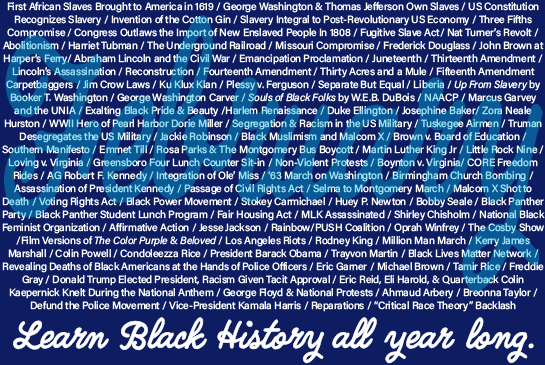

These laws make clear that enslaved persons consistently sought to educate themselves, despite penalties as severe as death, and that their efforts to do so were in affirmation of their humanity. For them, education was a revolutionary process that provided a counter-narrative to enslavement and subjugation, and centered their experiences and contributions in the telling of the American story. It is that legacy that remains, and in it the traditions of antiracist education and inclusive pedagogies that continue into the present day.

_____________

[1] William Goodell, The American Slave Code in Theory and Practice: Its Distinctive Features Shown by Its Statutes and Judicial Decisions (New York: American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, 1853), 319.

[2] Goodell, 321.

[3] Goodell, 321

[4] Goodell, 324

[5] Goodell, 322-323.

[6] Goodell, 319.