Backward Design

Erin Stapleton-Corcoran, CATE Instructional Designer

January 25, 2023

WHAT IS BACKWARD DESIGN? Heading link

Backward design is a framework for planning a lesson, weekly module, or an entire course. The term was introduced to curriculum design by Jay McTighe and Grant Wiggins in their book Understanding by Design (1998, 2005)

WHAT IS BACKWARDS DESIGN? Heading link

1

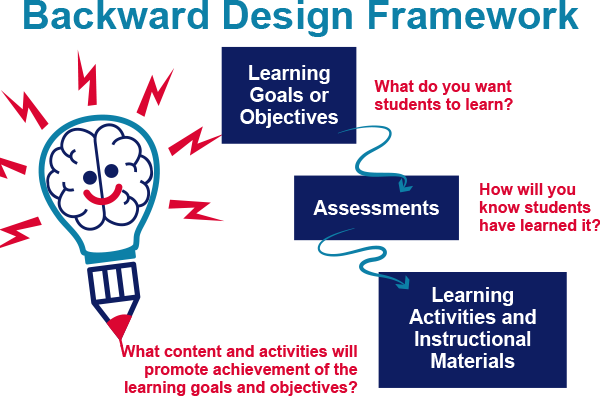

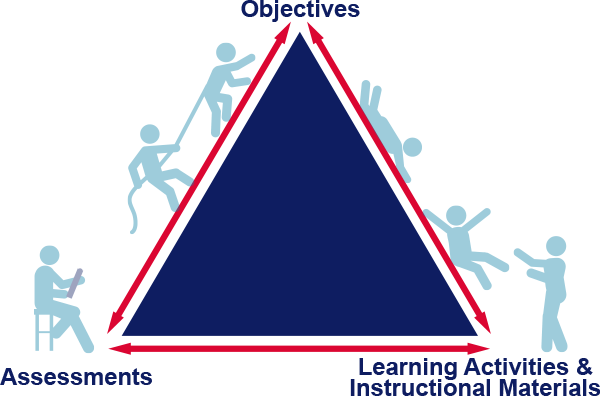

Backward design begins with the learning objectives of a lesson, module, or course — what students are expected to learn and be able to do — and then proceeds “backward” to create assessments that demonstrate students have learned what was outlined in the learning objectives. Finally, instructors create learning activities and instructional materials that align with and support the achievement of the learning objectives.

The Three Steps of Backward Design Are:

- Identify desired results. Upon completing a module or lesson in your course, or by the end of the semester, what knowledge, skills, or abilities should your students have achieved? In other words, what are course goals or learning objectives?

2

What content and activities will promote achievement of the learning goals and objectives?

3

- Determine acceptable evidence. What forms of documentation do you need to evaluate students’ progress toward proficiency of the learning objectives and course goals? In other words, what assessments will you incorporate into your class for students to demonstrate their learning?

- Plan learning activities and instructional materials. What engagement activities and direct instruction will you provide to support students’ achievement of the learning objectives and course goals? How will you scaffold the learning process? In other words, what learning activities and instructional materials will you utilize to move students progressively toward self-directed learning (Brookfield 2009) and achievement of the learning objectives and course goals?

Alignment is the degree to which learning objectives, assessments, learning activities, and instructional materials work together to achieve the desired course goals. The learning objectives that instructors create should direct the formative and summative assessments in their course, which will then determine which instructional materials and learning activities are used to support students’ achievement of the learning objectives.

4

Once you have worked through the three steps of backward design, you should make sure that all elements (objectives, assessments, learning activities, and instructional materials) align with each other.

WHY SHOULD I USE BACKWARD DESIGN IN MY COURSES? Heading link

Learner-Centered vs Content-Centered Approach

1

Traditionally, instructors have applied a forward or content-centered approach to designing lessons, modules, or courses. This approach begins with selecting content such as the sequential chapters of a textbook, followed by building learning activities to help students practice skills or acquire new knowledge about the selected content, and then creating assessments to determine whether or not students learned the content. This approach typically ends with crafting learning objectives to connect the content learned to the assessments.

A content-centered approach to instructional design risks creation of poorly-defined learning experiences where students aren’t clear on how the learning activities or learning objectives are supposed to support their learning of the content. After an exam, for instance, instructors might hear students express their frustration with statements such as, “that test wasn’t fair” or “that question came out of left field”.

2

What students are likely really saying is that they don’t understand how the test reflected the content they thought they studied or learned. Or perhaps they don’t feel they were able to adequately demonstrate what they did learn based on the types of questions they were asked on the exam. In other words, they don’t see an alignment between what they learned and what they were tested on.

Whatever the case may be, there is an alternative approach that helps instructors avoid these pitfalls and mitigate student frustrations with their learning experiences. Backward design takes a learner-centered approach to course design, facilitating the creation of more cohesive, clear, and intentional learning experiences for students. A learner-centered approach goes beyond engaging students in content and works to ensure that students have the resources and scaffolding necessary to fully understand the lesson, module, or course.

why cont Heading link

Benefits of Backward Design

1

A study focused on a group of library science instructors who used the backward design framework to revise a lesson on information literacy instruction in first year writing classes. Four assessment methods were used to measure the effectiveness of the new lesson plan: (1) a group activity completed in class, (2) a recommended follow-up assignment for students to complete after their library session, (3) librarian reflections, and (4) a faculty survey. Results indicated that backward design is a valuable planning model that may increase student learning and collaboration with faculty (Mills, Wiley & Williams 2019).

2

Buehl (2000) states that Backward Design offers these advantages:

- Students are less likely to become so immersed in the factual detail of a unit that they miss the whole point of studying the topic.

- Instruction focuses on global understandings and not on daily activities; daily lessons are constructed with a clear vision of what the overall “gain” from the lesson, module, or course is going to be.

- Assessment is designed before lesson planning, so that instruction is crafted to best facilitate student learning–students are not completing learning activities just for the sake of doing them (e.g., what students might refer to as busy work).

Backward Design emphasizes the following elements in your lessons, units or courses: Heading link

Backward Design Emphasizes the Following Elements In Your Lessons, Units or Courses:

-

Expectations

1

- Learning objectives are clearly defined.

- Student work is framed around questions & challenges that resonate with and are useful to students.

2

- Models of the outcomes expected of students are clearly articulated and shared.

-

Assessments

1

- Methods by which students are evaluated are clearly laid out and are not a mystery to solve.

2

- Assessment methods match the achievement targets of the learning objectives.

-

Learning activities

1

- Each student’s individuality and differences are acknowledged and accommodated through a variety of activities/methods.

2

- Students have choice and autonomy in the types of work they are asked to do.

- Learning is active/experiential to help students “construct meaning” (hands on, team based).

-

Instruction

1

- Instructor serves as a facilitator/coach to support the learner rather than as a lecturer to passive listeners.

- Instructor “uncovers” important ideas of the course by exploring important questions and real-world applications of knowledge and skills. (project-based learning).

2

- Teaching through passive lecturing is implemented as needed (“chunk the lecture” with learning activities interspersed with brief lectures 10-12 minutes in length. This length best aligns with student attention span, meaning they are more likely to listen and retain information).

-

Sequence & coherence

1

- Learning is scaffolded in “do-able” increments.

- Instructor established the purpose of doing something in the learning activity before implementing it.

2

- Expectations, assessment, activities, and instruction are melded into a cohesive learning experience (McTighe and Wiggins 2010).

HOW DO I IMPLEMENT BACKWARD DESIGN IN MY COURSES? Heading link

Backward design is implemented in three sequential stages:

Stage 1: Identify Desired Results

In the first stage of backward design, instructors identify what students should know, understand, and be able to do by the end of the course, lesson or module.

1

Identify the Big Ideas

Start with a focus on the “big ideas.” If you ran into one of your students years later, what are one or two big ideas or core ideas that you would hope they would remember from your course? Wiggins and McTighe describe big ideas as:

- A core concept, principle, theory, or process that should serve as a focal point for prioritizing content.

- An organizer for connecting important facts, skills, and actions. Big ideas connect discrete knowledge and skills to a broader intellectual frame and create a bridge to specific facts and skills.

- Transferable to other topics and contexts, issues, and problems.

2

- Found in the following forms that exist across the disciplines: concepts, themes, issues or debates, paradoxes, processes, problems or challenges, assumptions, and perspectives.

- An abstraction that is not immediately evident to students and which requires uncovering via direct instruction and well-designed learning activities (Wiggins and McTighe 2004, 69).

These “Big ideas” may be interpreted as course goals, which are broad statements of what you hope students will learn or take away from your class at the end. Course goals may use verbs associated with student outcomes that are not readily observable and do not lend themselves easily to measurement (e.g., know, understand, value, appreciate).

3

___

Transform the Big Ideas Into Essential Questions

After you have identified the “big ideas” you will transform these into essential questions. Wiggins and McTighe describe essential questions as:

- Not a right or wrong answer, but are meant to be debated. Essential questions promote inquiry and argument that foster inquiry and research. The student draws conclusions rather than recites facts.

- Designed to be thought-provoking for students, while also focusing on learning and the final assessment.

4

- Often address important issues, problems, or debates in a given discipline.

- Thought-provoking and generative. Essential questions often lead to additional questions that may cross disciplinary boundaries.

- Promote ongoing rethinking of big ideas and assumptions. (Wiggins and McTighe 2004, 91).

5

___

Craft Learning Objectives

Once you have identified the big ideas and essential questions, you will then translate these into learning objectives ,link to learning objectives teaching guide/>. A key to writing useful learning objectives is to make them SMART, i.e., specific, measurable, attainable, relevant (and rigorous, realistic), and timely. Five basic elements should be included in such objectives:

- who

- will do

- how much or how well

- of what

- by when

6

The objective should include 1) the subject (your students), 2) an action verb, and 4) a noun that describes an intellectual operation or physical performance, as well as 3) a criterion and 5) the conditions for completion (Thomas and Abras, 2016).

Bloom’s Taxonomy is a great tool in helping to identify action verbs appropriate for measurement. Another framework for constructing learning objectives is Fink’s Taxonomy of Significant Learning, which encompasses domains of knowledge and competencies beyond scholarly matters and also addresses humanistic dimensions of caring and lifelong learning.

Consult CATE’s Learning Objectives Teaching Guide for a fuller exploration of this topic.

8

___

Prioritize Content

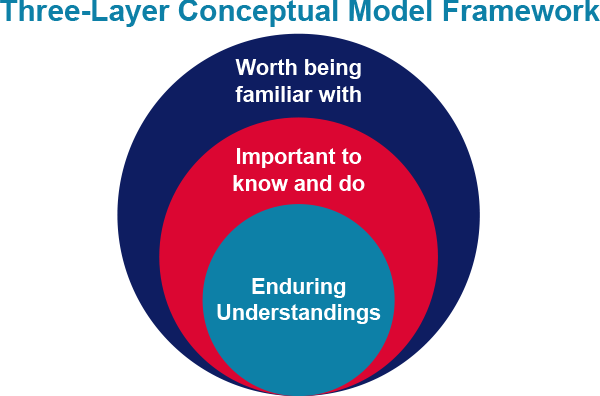

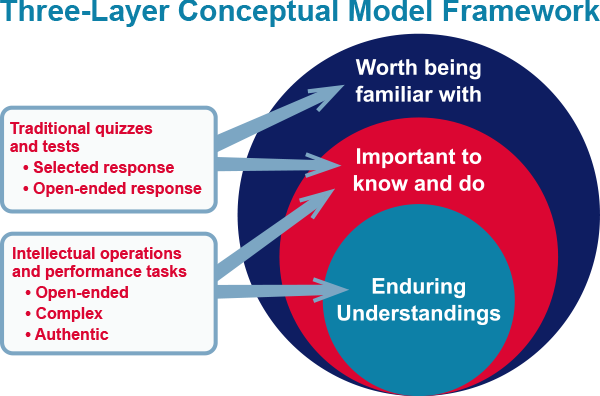

Because typically instructors have more content than can reasonably address within the available time frame, they must make choices. Wiggins and McTighe (1998) offer a three-layer conceptual model to aid in narrowing the focus of content when crafting learning objectives:

The outer circle of the framework identifies knowledge worth being familiar with or what students should “hear, read, view, research, or otherwise encounter.”

The middle circle identifies what is important to know such as important knowledge (i.e, facts, concepts, and principles), as well as skills, processes, strategies, and methods.

The inner circle identifies enduring understandings or big ideas that students should retain after they have forgotten many of the details (Wiggins and McTighe 1998, 9-10).

7

The three-layer conceptual model framework.

9

___

Guiding Questions For Identifying Desired Results:

- What should students hear, read, view, explore or otherwise encounter?

- What knowledge and skills should students acquire?

- What are big ideas and important understandings students should retain?

Determine appropriate assessments Heading link

Stage 2: Determine Appropriate Assessments

In the second stage of backward design, instructors create the assessments students will complete in order to demonstrate evidence of learning and even progress towards achievement of the learning objectives.

Types of Assessments

1

Assessment refers to the wide variety of methods or tools that educators use to evaluate, measure, and document the academic readiness, learning progress, skill acquisition, or educational needs of students.

There are two broad categories of assessments: summative and formative.

Summative assessments: assessment of your students’ learning – how much a student has learned or become proficient in knowledge and skills associated with your course. Characteristics of summative assessments include:

- Purpose for students: Evaluate learning, enter and graduate programs, and achieve professional credentials

- Graded: Usually (with incorrect and correct responses)

- Timing: Periodic, and typically occurs after learning activities

- Feedback: Often delayed, and in the form of a grade on an assessment

- Stakes: Usually high stakes (contributing to a large part of the student’s final grade) with one opportunity to perform well

Examples of summative assessments include exams, portfolios, presentations, written work.

2

Formative assessments: focus on assessment for learning. Formative assessments play a critical role in providing scaffolding for learning, opportunities to practice and build on prior knowledge, as well as integrating new concepts. Formative assessments help instructors and students gauge progress towards learning objectives to better equip students for studying and preparation for higher stakes summative assessments.

Characteristics of formative assessments include:

- Purpose for students: Enhance students’ metacognitive skills and studying behaviors, and guide their learning and skill-building in your course

- Graded: Sometimes (e.g., as participation points)

- Timing: Frequent and ongoing throughout the course

- Feedback: Immediate, with repeated opportunities for practice and reflection

- Stakes: Usually low stakes (contributing minimally to a student’s final grade) with multiple opportunities to improve

Examples include homework, group problem-solving, polling questions, brief writing exercises like one-minute papers, and draft presentations and reports.

Consult CATE’s Summative Assessment Teaching Guide and Formative Assessment Teaching Guide for a fuller exploration of these topics.

3

___

Three-layer Conceptual Model and Assessment Types

Wiggins and McTighe identify a link between the assessment format and the type of understanding students need to demonstrate. For example, if the goal is for students to learn basic facts and skills, traditional quizzes and tests might be the most appropriate type of assessment to use. However, when the goal is enduring understanding, more complex and authentic assessment strategies might be needed to assess student learning. The illustration below shows an alignment between specific assessment types and the different types of evidence they provide.

4

(Wiggins and McTighe 2004 141)

5

___

Six Facets of Understanding

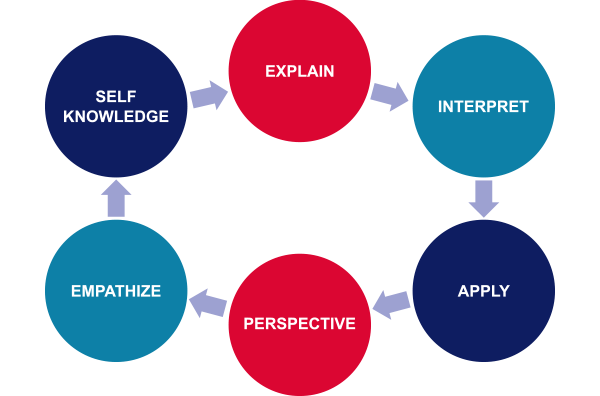

Wiggins and McTighe propose a framework called Six Facets of Understanding as a guide for building effective assessments. It is made up of six non-hierarchical ‘domains’ or ‘facets’ that they identify as indicators of understanding.

Understanding is revealed when students autonomously make sense of and transfer their learning through authentic performance (Wiggins and McTighe 2005 82-104). Wiggins and McTighe contend that students demonstrate true understanding when they can express their learning in one of six ways:

- Explain concepts by putting them into one’s own words, teaching it to others, justifying their answers, and showing their reasoning.

- Interpret by making sense of data, text, and experience through images, analogies, stories, and models.

- Apply what they know in diverse, real-world, and relevant contexts — the student can “do” the subject.

- Demonstrate perspective by seeing the big picture and recognizing different points of view.

6

- Empathize or find value in what others might find odd or implausible; make perceptions based on prior direct experience.

- Exhibit self-knowledge and show metacognitive awareness; should be aware of their position and what they do not understand as well as how that shapes their understanding. ⇒

7

___

Guiding Questions for Developing Assessments:

- How will I know if students have achieved the desired results?

- What will I accept as evidence of student understanding and proficiency?

- Do the assessments address the learning objectives of the course?

Stage 3: Plan learning activities and instructional materials Heading link

Stage 3: Plan Learning Activities and Instructional Materials

1

Now it is time to plan the lessons, determine reading assignments, method of instruction, and other classroom activities to support student learning. With students’ needs in mind, instructors can choose the most appropriate methods to help their students achieve the learning objectives.

In the past, classroom instruction has focused on the instructor and the ways in which the subject matter could best be presented to the student.

2

The emphasis was on “lectures” and “discussions” and the assumption was that learning largely consisted of a passive activity in which students received information and ideas from authoritative sources.

Research over the past several decades has shown that students learn more and retain their learning longer if they acquire it in an active rather than a passive manner. To learn more, consult CATE’s Active Learning Teaching Guide.

3

___

Learning Activities and the WHERETO Framework

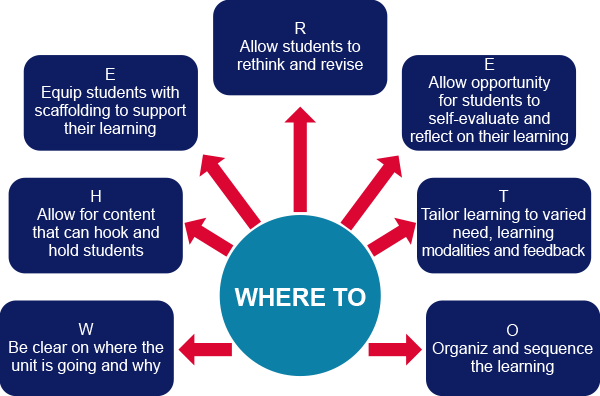

Wiggins and McTighe have created a six-part checklist built on the acronym WHERETO that consists of key elements that should be included in your instructional materials and learning activities.

W: How will you help your students to know where they are headed, why they are going there, and what ways they will be evaluated along the way?

H: How will you hook and hold students’ interest and enthusiasm through thought-provoking experiences at the beginning of each instructional episode?

E: What experiences will you provide to help students make their understanding real and equip all learners for success throughout your course or unit?

R: How will you cause students to reflect, revisit, revise, and rethink?

E: How will students express their understanding and engage in meaningful self-evaluation?

4

T: How will you tailor (differentiate) your instruction to address the unique strengths and needs of every learner?

O: How will you organize learning experiences so that students move from teacher-guided and concrete activities to independent applications that emphasize growing conceptual understandings as opposed to superficial coverage? (Wiggins and McTighe 2005, 195-226).

5

___

Guiding Questions For Developing Learning Activities:

- What enabling knowledge and skills will students need in order to achieve desired results?

- What activities will equip students with the needed knowledge and skills?

- What will need to be taught and coached, and how should it best be done?

- What materials and resources are best suited to accomplish these goals?

Backward Design and Alignment Heading link

1

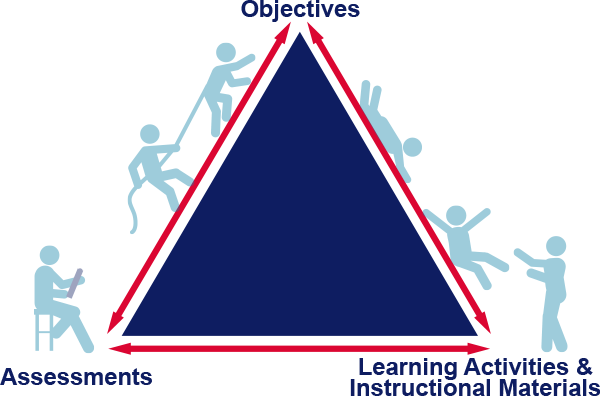

Objectives, assessments and learning activities are three cornerstones of backward design.

2

Backward Design and Alignment

A defining feature of Backward Design is its alignment between learning objectives, assessments and feedback, and learning activities and instructional materials.

alignment Heading link

-

Alignment of learning objectives to feedback and assessment

1

- Do the assessments you have built in your course address all learning objectives?

- Does the planned feedback give students information about their progress on all of the learning objectives?

2

- Are students given help in learning how to assess their own progress towards achievement of the learning objectives?

-

Alignment of learning objectives to learning activities

1

- Do the learning activities support all of the learning objectives?

2

- Are some activities “extraneous” (unrelated to any major learning objective)?

-

Alignment of learning activities to assessments and feedback

1

- Does the proposed feedback loop help students understand the criteria and standards used to assess their progress towards or achievement of the learning objectives?

2

- Do practice learning activities and associated feedback opportunities prepare students well for the final assessment process?

-

Course alignment: putting it all together

1

- Do your learning objectives state what you want students to be able to do at the end of your course?

- Will your assessments help you understand if students are meeting your learning objectives?

2

- What methods are you using in your course? Are they supporting students in reaching your objectives?

- Where are there gaps in your course alignment?

Alignment and course mapping Heading link

Alignment and Course Mapping

When developing your course within a Backward Design framework, it is important to map out your course learning objectives, assessments, and learning activities and instructional materials to ensure alignment across the elements. We suggest using CATE’s Course Map Planning Document to guide your progress.

HOW TO USE/CITE THIS GUIDE Heading link

- This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International.

- This license requires that reusers give credit to the creator. It allows reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, for noncommercial purposes only.

Please use the following citation to cite this guide:

Stapleton-Corcoran, E. (2023). “Backwards Design.” Center for the Advancement of Teaching Excellence at the University of Illinois Chicago. Retrieved [today’s date] from https://teaching.uic.edu/resources/teaching-guides/learning-principles-and-frameworks/backward-design

REFERENCES Heading link

-

References

1

Buehl, D. (2000, October). Backward design; Forward thinking. Education News.

Kelting-Gibson. (2005). Comparison of Curriculum Development Practices. Educational Research Quarterly, 29(1), 26–.36

McTighe, J., & Wiggins, G. (2004). Understanding by design: Professional development workbook. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development.

McTighe, Jay and Wiggins, Grant (2010) Schooling by Design: Identifying School-Wide Principles of Learning. https://jaymctighe.com/downloads/Learning-Principles-handouts-set1.pdf Accessed Jan 15, 2022.

2

Mills, J., Wiley, C., & Williams, J. (2019). “This Is What Learning Looks Like!”: Backward Design and the Framework in First Year Writing. portal: Libraries and the Academy 19(1), 155-175.

Wiggins, & McTighe, J. (1998). Understanding by design. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Wiggins, & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design (Expanded 2nd ed.). Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES Heading link

-

Additional Resources

1

Fox, & Doherty, J. (2012). Design to learn, learn to design: Using backward design for information literacy instruction. Communications in Information Literacy, 5(2), 144–155.

Hills, Harcombe, K., & Bernstein, N. (2020). Using anticipated learning outcomes for backward design of a molecular cell biology Course‐based Undergraduate Research Experience. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education, 48(4), 311–319.

McTighe, & Willis, J. (2019). Upgrade your teaching : understanding by design meets neuroscience. ASCD.

Mills, Wiley, C., & Williams, J. (2019). “This Is What Learning Looks Like!”: Backward Design and the Framework in First Year Writing. Portal (Baltimore, Md.), 19(1), 155–175.

Neiles, & Arnett, K. (2021). Backward Design of Chemistry Laboratories: A Primer. Journal of Chemical Education, 98(9), 2829–2839.

2

Reynolds, & Kearns, K. D. (2017). A Planning Tool for Incorporating Backward Design, Active Learning, and Authentic Assessment in the College Classroom. College Teaching, 65(1), 17–27.

Richards, Jack (2013). Curriculum approaches in language teaching : forward, central, and backward design. RELC Journal, 44(1), 5–33

Srikongchan, Kaewkuekool, S., & Mejaleurn, S. (2021). Backward Instructional Design based Learning Activities to Developing Students’ Creative Thinking with Lateral Thinking Technique. International Journal of Instruction, 14(2), 233–252.

Wiggins, & McTighe, J. (2011). The understanding by design guide to creating high-quality units. ASCD.

Wright, Hornsby, L., Marlowe, K. F., Fowlin, J., & Surry, D. W. (2018). Innovating Pharmacy Curriculum through Backward Design. TechTrends, 62(3), 224–229.