Student Feedback

Leveraging Student Feedback on Teaching

Crystal Tse, CATE Associate Director

January 24, 2022

WHAT?

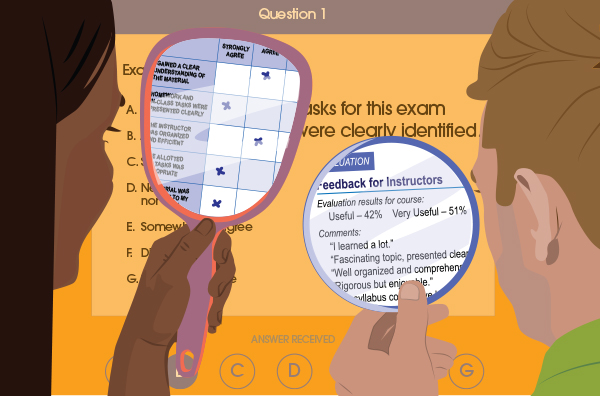

Collecting student feedback on your teaching is one way to assess the impacts of your teaching and use data to inform improvements to your teaching.

column 1

Student feedback can be collected in a variety of formats:

- Before, during, and after individual class periods

- In a mid-semester questionnaire

- After the course has finished in student course evaluations

- As part of your formative assessments, which are lower-stakes learning activities or assignments that contribute minimally to students’ grades and provide both students and instructors with feedback on students’ progress with the course material.

In this teaching guide, you will learn about:

- Benefits of collecting, reflecting, and acting upon student feedback to enhance your teaching

- Ways to set up your classroom climate to be conducive to gathering constructive, useful feedback with high response rates

- Strategies and tools to collect, analyze, and respond to student feedback

column 2

.

WHY?

Why Collect Student Feedback During the Course?

Collecting student feedback throughout your course comes with several benefits to teaching teaching (Angelo & Cross, 1993; Brookfield, 2017). You can:

column 1

- Make changes in real time. You can proactively address any instructional and/or classroom management/logistical issues.

- Build trust and rapport with your students. By soliciting and thoughtfully responding to students’ feedback, students can see that you care about, and are invested in, their learning.

- Develop students’ metacognitive thinking skills (Schraw & Moshman, 1995). When collecting feedback during class, you not only assess the impact of your teaching strategies, but students can also become more aware of their own learning processes – their strengths and areas for improvement, study skills that could be strengthened, and what they could do differently to improve their learning experience in your course.

column 2

- Foster a sense of community among your students. Students, especially in larger classes, can feel less anonymous if they feel that their voices are being heard by their instructor.

- Help students see the rationale behind your teaching strategies and activities. When reporting out student feedback on your class activities, students can see the value of various class activities to different students. What may not work for one student may be working very well for others. This helps to reduce student resistance to your use of teaching strategies in a class that don’t always align with student learning preferences.

WHY

column 1

Limitations of Student Course Evaluations of Teaching

A common source of student feedback on your teaching, which is oftentimes used for evaluative purposes and thus may also be considered a rather high-stakes assessment of our teaching, is students’ course evaluations collected at the end of a semester. Recent research has called into question the validity of student course evaluations on measuring teaching effectiveness (e.g., Spooren et al., 2013). For example, Stark & Freishtat (2014) cite measurement issues with student course evaluation ratings, such as overall “teaching effectiveness” ratings being influenced by irrelevant factors, including the time of day of class sessions and the type of course. They also raise concerns about how course evaluation statistics are typically and misleadingly reported (e.g, reporting only means and not acknowledging low response rates, and thus not accounting for the full and possibly multimodal distribution of scores) and incorrectly analyzed (e.g., comparing means for individual instructors to departmental or college averages). Recent meta-analyses also show no correlation between student preferences for learning as surmised from course evaluations and actual student learning (Uttl et al., 2017). Lastly, some research shows bias in student responses on course evaluations that disproportionately and negatively impact women and instructors from marginalized groups (Boring et al., 2016; Kreitzer & Sweet-Cushman, 2021; MacNell et al., 2015).

When used for formative purposes — that is, to inform improvements to your teaching — there is one key limitation to using the information from student course evaluations as the sole source of data. Because this feedback is collected at the end of the course, it cannot be used to make data-informed, mid-semester adjustments to your teaching plan.

column 2

By contrast, collecting feedback during the course allows you to make timely changes to address any instructional or classroom management/logistical concerns.

All of these factors should be taken into consideration when using some of the student course evaluation data in the evaluation of teaching. Certain questions, such as survey items inviting students to rank or comment on the overall effectiveness of their instructors or overall quality of the course, are particularly problematic whether used for formative or summative purposes. To work around the faulty nature of course evaluations, consider using the data from these instruments as formative feedback on your teaching, focusing on some of the more common themes that emerge from qualitative responses and expanding the statistics considered when examining the quantitative responses to account for low response rates and distributions that deviate from normality (e.g., means with standard deviations, medians, box plots with distributions of scores, nonparametric statistics). It is equally important to consider collecting data from different sources (e.g., students, peers, education literature, self-reflection) to ensure that all the feedback you are collecting reveals a similar story and outcomes. This process — using at least three points of data to inform educational decisions about your teaching — is referred to as triangulating student feedback from different data sources (Heath 2015; Salkind 2010).

HOW?

column 1

Setting Up Your Classroom Climate

Here are some things you can try to set up your course and classroom environment to be conducive to student feedback (Ambrose et al., 2010, Svincki, 2001):

- Respond to students’ feedback. It is important to close the loop on the feedback cycle. You can increase students’ motivation to give you feedback by affirming their belief that their feedback will make a difference in your teaching and their learning experience.

- Reframe office hours as drop-in hours. Shape an open-door policy in which students can approach you with constructive feedback.

- Set expectations up front about how feedback will be part of your course. Discuss the importance of giving and receiving feedback in the learning process and how feedback can facilitate their learning (e.g., as a writer, professional, scientist, artist, etc.).

- Model what effective feedback looks like, and give students opportunities to practice giving feedback (e.g., group work, peer review of work). Try to give them feedback as soon as possible after the learning activity is complete.

column 2

- Provide students with choices for formats for activities and assignments. This can give students agency, or a voice in their learning, in your course. It can also give you data on students’ learning preferences to help you decide on the format for the assignments in the next offering of the course. In addition, this strategy supports universal design for learning (increasing the accessibility and flexibility of your course to reach diverse learners) and promotes student engagement.

Strategies and Tools

Classroom assessment techniques (CATs) are strategies you can use to collect real-time feedback on student understanding to make adjustments to your teaching methods (Angelo & Cross, 1993). Click on each accordion heading below to learn more about different strategies that you can use, depending on your questions and goal for collecting feedback.

h4 titles

What do my students already know?

column 1

- Background knowledge probe: At the beginning of your course, or before starting a unit or module in your course, you can probe your students’ prior knowledge and misconceptions of the course content by administering a short questionnaire. Students can reflect upon what they already know about the content, and you can tailor your learning activities to meet where your students are with the material, ensuring everyone gets an opportunity for an equitable start in your course.

Online tools you can use to construct questionnaires: Google forms, Qualtrics

column 2

- Pre-course questionnaire: At the beginning of the course (during the first day or week of classes), survey your students to get to know who they are: strengths and areas to improve, academic and career goals, and motivation and any concerns or expectations about taking your course.

How do students find the pacing of my class?

column 1

- Polling: You can use polls to gauge the pacing of your class (e.g., “are we ready to move onto the next concept”?), while at the same time keeping responses anonymous. As a no-tech option, you might opt to use a thumbs up or thumbs down approach to gauge readiness to move on to the next topic, or ask students to pull up different colored or patterned pieces of paper (e.g., red or solid pattern to stop and give another example, yellow or singled dotted line to slow down, green or solid line to keep going). In addition, you can also ask multiple choice questions related to readings or course content to assess how prepared students came for the class session.

column 2

Paper tools: ABCD cards (darker ink that is easier to see with large classes / less ink to print) you can print and distribute to students for them to answer questions by holding up cards indicating A, B, C, or D for you to see.

Online tools you can use for polling students:

- UIC supported license: Zoom, iClicker

- Other recommended applications*: Poll Everywhere, Mentimeter, Kahoot!, Plickers, ABCD cards Mobile app

*Please note that these applications are not associated with a UIC license and thus may have costs associated with their use that are not covered by the university. There also may be limited ed tech support available for set up and troubleshooting. That said, these applications are commonly used in college courses. Please just be mindful that their use does not violate FERPA policy.

What do students think about my assessments?

column 1

- Exam or assignment wrappers: After students finish an assessment, or receive their score on an assignment or exam, ask students to reflect upon how they prepared (e.g., amount of time they spent preparing, study strategies used, what knowledge or skills they applied), what questions or problems on the assessment that they found challenging, and strategies they will use to try to improve their performance on the next assessment. You should return this wrapper to students before their next assessment so that they can revisit the strategies they had planned on using. As their instructor, it is important that you also provide students with suggestions for effective study strategies tailored to your course content. There are resources on evidence-based study strategies that you should share with your students (“Six Strategies for Effective Learning” by the Learning Scientists; “What works, what doesn’t” by Dunlosky et al., (2013)).

column 2

Online tools you can use to create wrappers: Google forms, Qualtrics

What are my students thinking about?

column 1

- Brief reflective writing activities:

- Exit slip: Before students leave class, ask students to take 1 minute to answer one question about their experience with the class content or learning activities.

- Muddiest point: At the end of the class, ask students to take a few minutes to write about a point in the class they still do not understand and need clarification or more information and practice applying the concept.

- 3-2-1: Ask students to respond to the following prompt: 3 ideas they learned about, 2 examples for how the ideas could be applied, 1 muddiest point.

- Think-pair-share: After asking your question, give students a minute to reflect and write down their response. Next, ask students to discuss in pairs (or small groups of 3-4 students). Then debrief with the entire class by asking students to share what they discussed with their partner or small group using chat, verbal, or written responses on a shared document.

column 2

- Weekly wrap-up: In a brief questionnaire, ask students to assess their own learning progress for that week. You can also ask students for feedback on the course materials. See a few examples on how this can be done by UIC instructors (weekly journals by Professor Anne Magi from the College of Business and weekly surveys by Professor Virginia Reising from the College of Nursing)

Online tools you can use: Google forms, Google docs, Qualtrics

How do I gather more comprehensive feedback on my students’ learning experiences?

column 1

To obtain a more nuanced and comprehensive view of your students’ learning experiences in your course, consider strategies intended to help you collect more intensive, detailed feedback:

- Midterm feedback questionnaire (Payette & Brown, 2018): You can send a brief questionnaire in the middle of the semester surveying students’ learning experiences. You can also make this a collaborative process by asking students to contribute anonymously on a shared document (e.g., Google document, Padlet)

- Colleague facilitated student focus group: Midway through the semester, ask a colleague to facilitate a short (10-15 minute) focus group at the end of one of your class sessions, and then provide you a summary of anonymous student comments.

column 2

Here are some examples of questions you can use on your midterm feedback questionnaire or to facilitate a focus group:

- What would students like the instructor to start, stop, and continue to do in the course?

- What is working well for you in this course?

- What challenges are you experiencing in this course in terms of your learning?

- What could I do differently to support your learning in the course?

- How much time are you spending on this course outside of class?

- What could you do differently to improve your learning experience in this course?

- How much do the following class activities support your learning? (e.g., lectures, polling questions, small group discussion, homework assignments, etc.)

- You can also ask students questions about the classroom climate, such as: Are you comfortable sharing your comments or asking questions in class?; How connected do you feel to your peers and instructor in this class?

Analyzing and Responding to Student Feedback

Analyzing and Responding to Student Feedback

Analyzing and Responding to Student Feedback

Now that you have collected feedback from students, what do you do with all these data? Here are a few steps and tips to consider when analyzing and responding to your students’ feedback:

Analyzing and Responding to Student Feedback

Analyze the feedback

column 1

Group feedback into categories that make sense for you (e.g., positive vs. negative comments or responses, common themes). When reflecting on the feedback, consider the feedback holistically and focus on consistent trends.

column 2

Filter out any unhelpful criticism or outliers, and give yourself time and space to respond if you find any of the feedback challenging or upsetting. Consider implementing suggestions that are being made by multiple students.

Follow up with your students

column 1

Talk to your students about your feedback, whether in a verbal summary or tabulating responses (Google Forms can visualize quantitative responses for you, and you can use word cloud generators to visualize open-ended responses). Let students know aspects of the course you will and won’t change, and your rationale.

column 2

You do not have to implement all the feedback you receive — consider teaching choices that are based in the literature, contribute to an inclusive learning environment, and that will help students achieve or master the learning objectives in your course. Explain your choices to your students backed by the evidence.

Implement the changes

column 1

To close the loop on the reflective teaching cycle, implement some of the changes suggested by students. Depending on the feedback you receive, you can implement them now, during the course, or in your next offering of the course. Be transparent with your students about your plan for implementing (or not implementing) changes and briefly explain why or why not.

column 2

For example, this can be an opportune time to share the lack of correlation between learning preferences and actual learning gains, justifying why you incorporate learning activities that may not be everyone’s favorite (e.g., active learning, group work). You can also point out the diversity of responses and how what may not work for some students is a powerful motivator to engage others and that your job is to balance this out throughout the semester.

Considerations for your course context

Considerations for your course context

Considerations for your Course Context

When making your plan to incorporate the collection of student feedback in your course, consider the following questions:

- What kind of feedback are you looking for? Your goals for feedback determine the type of classroom assessment technique you use. For example, you could use polling or a brief writing activity to gather feedback on a specific instructional strategy that you are trying for the first time. You can use a longer midterm feedback for comprehensive feedback on your whole course and methods of instruction.

- How much time, resources, and support do you have? It is not necessary to implement all the student feedback strategies, and in every class session. What is feasible given your time and resources? How might TAs or learning assistants be able to assist you?

column 2

- Are you teaching a large-enrollment course? Consider the frequency with which you want to administer the feedback strategies and analyze the data. For example, you could sample a portion of your class and rotate the week in which students complete the assessments.

- In what modality are you teaching? For in-person, on campus classes, pen/paper is relatively easy to administer, typically resulting in a high student response rate. However, educational technology tools can give you a plethora of options to gather feedback from your students. Consider trying different methods and see which ones work best for you and your students. Make sure you set aside time for students to give you feedback; asking them to do this outside of class likely will not result in a high response rate unless you incentivize completion with participation points.

HOW TO USE/CITE THIS GUIDE

- This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International.

- This license requires that reusers give credit to the creator. It allows reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, for noncommercial purposes only.

Please use the following citation to cite this guide:

Tse, Crystal (2022). “Student Feedback: Leveraging Student Feedback on Teaching.” Center for the Advancement of Teaching Excellence at the University of Illinois Chicago. Retrieved [today’s date] from https://teaching.uic.edu/resources/teaching-guides/reflective-teaching-guides/student-feedback/

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

column 1

column 1

Examples of CATs:

- Example techniques including description, what to do with the data, and time required (Indiana University Bloomington)

- Common techniques with alternatives and online options (Northern Illinois University)

column 2

- Categorized by what you want to assess and how it’s done, used, and time required (Iowa State University)

- 50 CATs categorized by what you want to assess from Angelo, T., and Cross, K. P. (1993).Classroom Assessment Techniques : A Handbook for College Teachers. (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Example of a weekly check-in survey

column

Example of a weekly check-in survey:

- Critical incident questionnaire (CIQ): Updated template (pg 6) from Brookfield, S. D. (1995). Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass

Examples of midterm student feedback survey questions

column 1

Examples of midterm student feedback survey questions:

- Questions by type of class (general, laboratory, discussion-oriented, group work-oriented) (University of Princeton)

- Sample midterm survey form (University of California, Los Angeles)

REFERENCES

REFERENCES

column 1

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., DiPietro, M., Lovett, M. C., & Norman, M. K. (2010). How learning works: Seven research-based principles for smart teaching. John Wiley & Sons.

Angelo, T., and Cross, K. P. (1993). Classroom Assessment Techniques : A Handbook for College Teachers. (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Boring, A., Ottoboni, K., & Stark, P. B. (2016). Student evaluations of teaching (mostly) do not measure teaching effectiveness. ScienceOpen Research.

Brookfield, S. (2017). Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher. (2nd ed.). Jossey Bass.

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). What works, what doesn’t. Scientific American Mind, 24(4), 46-53.

Kreitzer, R. J., & Sweet-Cushman, J. (2021). Evaluating student evaluations of teaching: A review of measurement and equity bias in SETs and recommendations for ethical reform. Journal of Academic Ethics, 1-12.

Heath, L. (2015). Triangulation: Methodology. In J. D Wright (Ed), International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences (pp. 639-644). Elsevier Ltd.

MacNell, L., Driscoll, A., & Hunt, A. N. (2015). What’s in a name: Exposing gender bias in student ratings of teaching. Innovative Higher Education, 40(4), 291-303.

column 2

Payette P. R., & Brown, M. K. (2018). Gathering mid-semester Feedback: Three variations to improve instruction. IDEA Paper #67.

Salkind, N. (2010). Triangulation. In Encyclopedia of Research Design.

Schraw G., & Moshman D. (1995). Metacognitive Theories. Educational Psychology Review, 7(4), 351-371.

Spooren, P., Brock, B., & Mortelmans, D. (2013). On the validity of student evaluation of teaching the state of the art. Review of Educational Research, 83(4), 598-642.

Stark, P. B., & Freishtat, R. (2014). An evaluation of course evaluations. ScienceOpen Research.

Svinicki, M. D. (2001). Encouraging your students to give feedback. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 87, 17-24.

The Learning Scientists: Six Strategies for Effective Learning: Materials for Teachers and Students.

Uttl, B., White, C. A., & Gonzalez, D. W. (2017). Meta-analysis of faculty’s teaching effectiveness: Student evaluation of teaching ratings and student learning are not related. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 54, 22-42.