Note-taking

Erin Stapleton-Corcoran, IDMPS instructional designer

October 30th, 2023

Note-taking support is an essential component of inclusive and equitable teaching practices, aiming to provide equal opportunities for all students in our classrooms. This teaching guide explores proactive strategies for instructors, to enhance students' note-taking skills, structure lectures for effective note-taking, reduce the need for individual note-taking accommodations for students, and employ inclusive techniques such as guided and collaborative note-taking to improve note-taking outcomes for diverse learners.

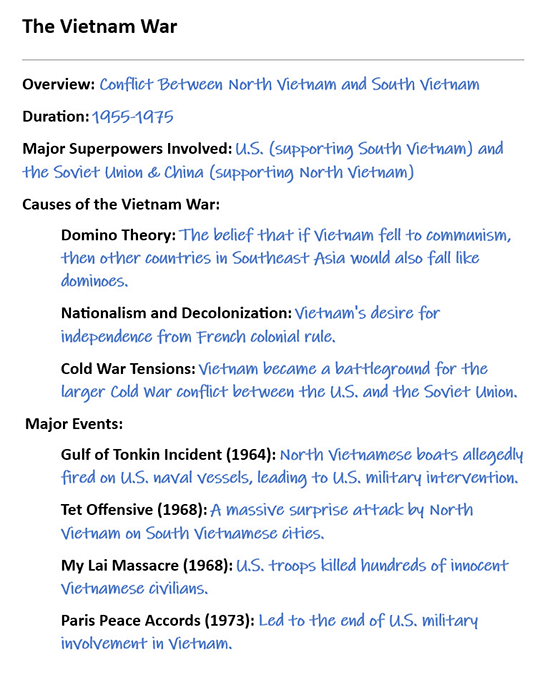

WHAT IS NOTE-TAKING?

4

Note-taking is the process of writing down, typing, or crafting graphical representation of information for later reference. Students take notes while participating in lectures or meetings, reading books or articles, listening to podcasts or audio files, or viewing videos or other visual media. Note-taking produces a written record for later review, while also promoting encoding of information (Kobayashi 2006).

Suritsky and Hughes (1991) identify four steps in note-taking:

- 1. Listening

- 2. Cognitive processing, which involves:

- Understanding each learning concept

- Connecting one’s understanding of a learning concept with existing knowledge or other learning concepts

- 3. Recording learning content in written, typed, or graphic form

- 4. Reviewing recorded learning content

2

Note-taking produces a written record for later review, while also promoting encoding of information.

Note-taking Methods

Note-taking Methods

1

There are many different note-taking methods and styles. While students may find a particular method more appropriate for specific note-taking tasks, each of these methods can be used in a variety of contexts, for recording information from different sources (e.g., lectures, meetings, written text, videos, audio recordings), or in different instructional modalities (e.g., in person, online asynchronous, or online synchronous).

2

Note: the note-taking methods described below can also be used in a variety of combinations.

methods

List Method

The list method of note-taking involves recording information as a sequential list of ideas as they are presented. This can be in the form of short phrases or full paragraphs that delve into each idea in more detail. The list method works well for jotting down specific facts, names, dates, or other details. It can be beneficial when used in combination with other strategies. For example, initial notes can be taken using the list method, then restructured into an outline or concept map during the review process.

Click here for an example and template of list note-taking: List note-taking template

avantages/disadvantages

1

Advantages:

- Simplicity: The list method is straightforward, making it a comfortable starting point for students unfamiliar with other note-taking techniques.

- Flexible structure: The list method doesn’t demand hierarchical organization, making it adaptable for fast-paced lectures or discussions without a clear hierarchy.

- Active engagement: List-making requires attention and promotes engagement with the material being presented.

- Visual clarity: Lists present information in a clear and readable format.

2

Disadvantages:

- Lack of hierarchy: Since lists generally lack the hierarchical structure of other methods, students may have difficulty distinguishing between main ideas and supporting details.

- Excessive writing: This method can lead to an overemphasis on writing, potentially causing students to miss important points as they struggle to note down everything.

- Limited information processing: The list method focuses more on capturing as much of the lecture as possible in real-time rather than processing and understanding the material, which may affect long-term retention and understanding.

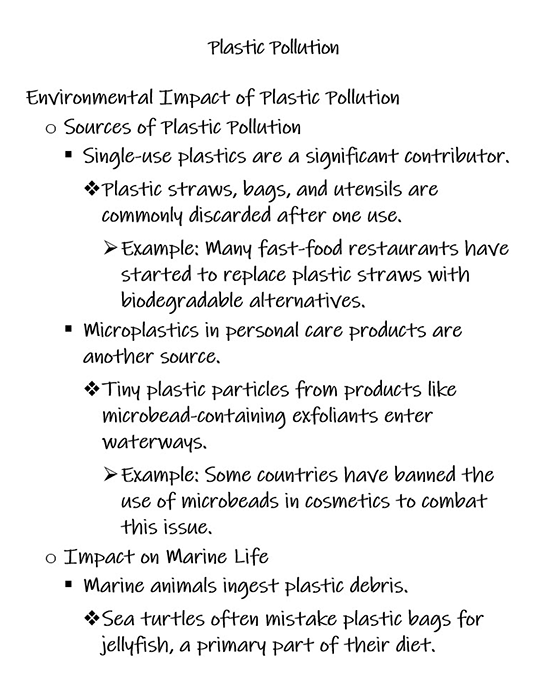

Outline Method

The outline method of note-taking is a structured technique that involves organizing information in a hierarchical format. The main topics are written as top-level entries, and supporting ideas are indented and listed beneath the corresponding main concepts. The outline method presents relationships between ideas, showing how different pieces of information connect and fit together. This method works well in organized lectures or for instructional materials that follow a clear hierarchy. Here are the steps to creating outline notes:

- Create left-side headings: Headings represent a main idea or topic and are more general in scope.

- Indent for subheadings: Subheadings represent subtopics under the main idea or topic.

- Further indent for points: Points are supporting thoughts or facts for subheadings.

- Another level of indentation for sub-points: Sub-points are additional details about a point in your notes.

- Continue adding new headings or subheadings for different main ideas or topics.

Click here for an example and template of outline note-taking: Outline note-taking template

advantages/disadvantages

1

Advantages:

- Organized structure: The outline method presents a hierarchy of information, which allows students to distinguish between main ideas, supporting details, and minor points.

- Effective review: The structured format simplifies the revision process, making it easier for students to locate specific pieces of information.

- Promotes understanding: By requiring students to categorize information according to its importance, the outlining method facilitates a deeper understanding of the material.

- Adaptability: Outlines can be expanded or modified to accommodate additional details or subpoints that emerge during a lecture or while studying.

2

Disadvantages:

- Requires concentration: The outline method requires active engagement and the ability to understand and categorize information in real time, which may be difficult during fast-paced lectures.

- Hierarchy anxiety: Students may struggle with determining the level of importance of specific pieces of information.

- Lack of flexibility: This method can be hard to adapt for discussions or lectures that don’t follow a clear hierarchy of learning concepts. Outlines are less effective for subjects that involve complex interrelationships between concepts.

- Time-consuming: It may take more time to create an outline than it would to take notes in other methodologies.

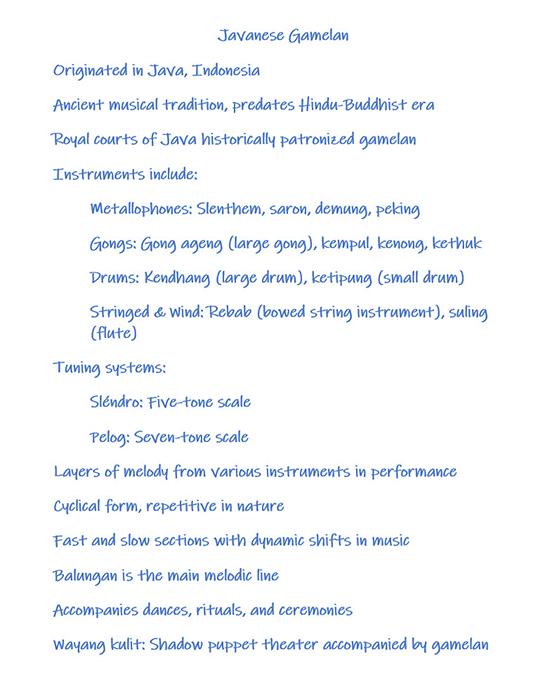

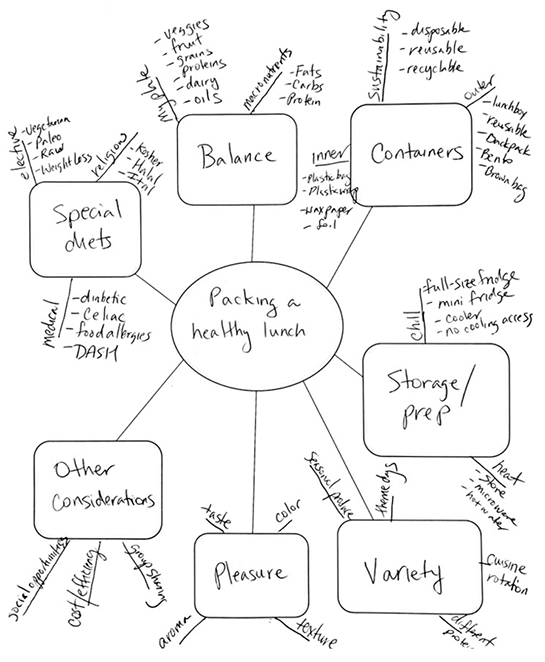

Concept Map

The concept map method of note-taking involves drawing a diagram that visually organizes information. The main topic is usually placed in the center of the map, and related ideas branch out from the main topic. This technique can effectively show relationships and hierarchies between ideas. Concept maps work well for learning situations where understanding the relationships between ideas is crucial, such as studying complex topics with interconnected ideas, brainstorming sessions, or reviewing materials to synthesize understanding. However, concept maps might not be the best choice for rapidly paced lectures or for people who prefer a more structured, linear format.

Click here for an example and templates of concept map note-taking: Concept map template and example.

This template contains two examples of concept maps, but there are countless concept map layouts and formats. You may find additional concept map options at Lucidspark and Canva, for example.

Concept Map

1

Advantages:

- Visual learning: Concept maps appeal to visual learners, as this method can help students see connections between ideas more clearly.

- Creative engagement: Concept maps can be more engaging and creative than linear note-taking styles, which may increase student interest and information recall.

- Flexible structure: Concept maps are easily expandable and adaptable, allowing for the addition of new information or connections as understanding deepens.

- Facilitates understanding: By mapping the relationship between ideas, this method can aid in understanding complex concepts and structures.

2

Disadvantages:

- Time-consuming: Creating a detailed concept map can be more time-consuming than other note-taking methods, which is especially challenging during a fast-paced lecture.

- Challenging for complex topics: It can be challenging to create a concept map for topics with complex interrelations or without a clear structure.

- Requires space: Concept mapping requires more space than linear methods, which can be a disadvantage when space is limited.

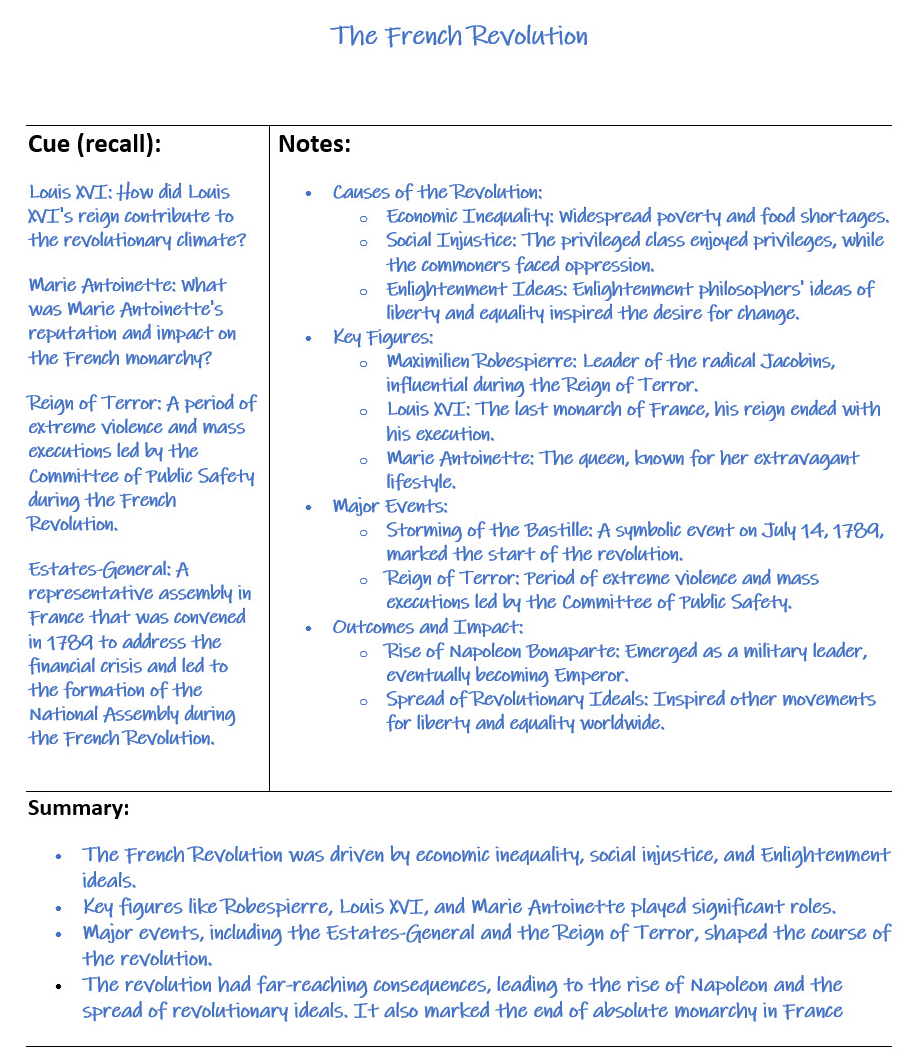

The Cornell Method

The Cornell Method of note-taking, developed in the 1950s by Professor Walter Pauk at Cornell University, is a systematic approach designed for condensing, organizing, and reviewing notes (Pauk 2010). The Cornell Method is suitable for a wide variety of learning situations, particularly in lectures or reading assignments with a clear structure. It’s especially beneficial for subjects that require comprehensive review for exams, as the method emphasizes active recall. This method might be less effective for brainstorming sessions or for understanding complex, interconnected concepts where a visual representation, like a concept map, might be more appropriate.

The structure of the Cornell method involves dividing a page into four sections:

- Header: A small box across the top, which contains identification information like the course name and the date.

- Notes column: This is a wider column on the right hand portion of the page. It is used to capture main notes using any preferred method.

- Cue column: A narrow column on the left (about one-third of the page) called the “cue” column. This column is used both during the class and when reviewing notes and intended for jotting down main ideas, keywords, questions, and clarifications.

- Summary column: Area at the bottom of the page used for summarizing the class content in your own words after the session. This summarization aids in making sense of the notes for future reference, supporting recall, and studying.

- Click here for an example and template of Cornell note-taking: Cornell note-taking template

The Cornell Method

1

Advantages:

- Organized structure: The Cornell Method provides a clear and organized structure that can help students locate and review information.

- Active engagement: This method encourages active engagement, as it involves generating questions and summarizing information.

- Facilitates review: This format is excellent for review, with cues and questions serving as prompts for active recall of information.

- Efficient: The Cornell method facilitates efficiency, as it encourages concise note-taking, which minimizes the risk of including unnecessary information in one’s notes.

2

Disadvantages:

- Requires discipline: The Cornell Method demands discipline in maintaining the structure and in consistently developing cues and summaries.

- Time-consuming: The method can be time-consuming, particularly the process of generating cues and summaries.

- Lack of flexibility: This method might be less suitable for lectures or discussions that don’t follow a linear or hierarchical structure, as it doesn’t readily allow for visual mapping of information.

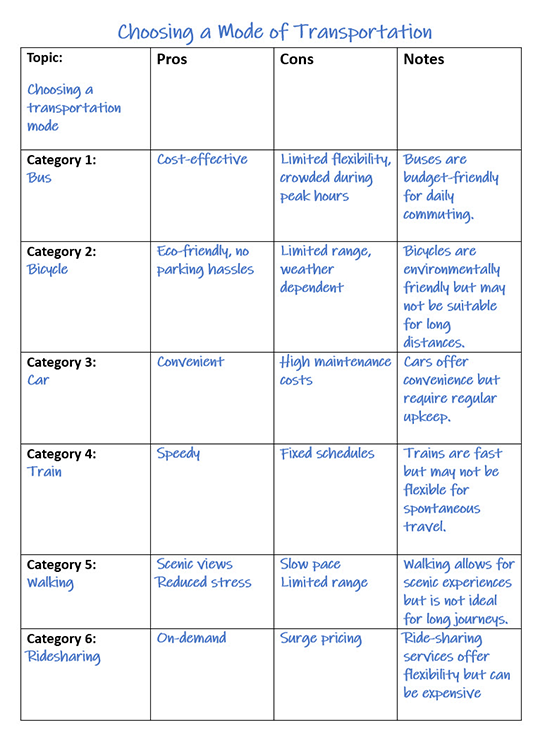

Charting Method

The Charting Method of note-taking is a visual strategy that involves creating a table or chart to organize information. The columns and rows are labeled with categories related to the topic, and the corresponding details are filled in as the student engages in the lecture or interacts with instructional materials. The charting method is particularly useful in learning situations where information can be organized into categories, such as comparing different theories or concepts, summarizing a series of events or steps, or classifying items or ideas. This method is less effective for recording materials that follow a story or progression of information.

Click here for an example and template of the charting method of note-taking: Charting note-taking template

Charting Method

11

Advantages:

- Organized and concise: The charting method provides a clear, concise layout that facilitates easy review of information.

- Comparison and contrasting: This method works well for showing relationships, such as comparing and contrasting different ideas or concepts.

- Visual: Charting offers a visual representation of information that can be beneficial for visual learners.

2

Disadvantages:

- Not well-suited for fast-paced lectures: Charting can be challenging to use, as creating and filling in a chart takes time.

- Requires prior knowledge: This method works best when you know ahead of time what categories will be useful.

- Limited details: Charting might not be suitable for capturing extensive details or complex concepts that don’t fit neatly into the table’s structure.

Guided Note-taking

Guided notes are handouts that outline the lecture content with blanks for key concepts, facts, or relationships that students fill in during the lecture. This helps students focus on the key points and engage more actively in the lecture (Chen and Zhou 2017). Guided notes align the process of note-taking with the principles of Universal Design for Learning, offering an inclusive learning environment for all students. Offering a detailed template via guided notes offers transparency and creates an equitable learning environment where all students are focusing on the same key elements. Guided notes are versatile across different disciplines and work equally well for in-person, online asynchronous, online synchronous, synchronous distributed, and hybrid course

Please visit the HOW section of this teaching guide to learn more about crafting guided notes and in which context their use is most appropriate.

Click here for an example and template of the guided method of note-taking: Guided note-taking template

Collaborative Note-taking

1

Collaborative note-taking is a pedagogical strategy where students take notes on the same material and then share, compare, and consolidate their notes. This method fosters collective learning and knowledge dissemination, while simultaneously calling on individual students to document, share, compare, and consolidate their insights on the same material. The collaborative and individual aspects enhance the depth and breadth of the information documented.

Collaborative note-taking works best in learning situations with group activities and discussions, such as study groups, project-based learning, or cooperative learning environments. It can also be beneficial in large lectures where a lot of information is being shared, as it increases the likelihood of capturing all important points.

Please visit the HOW section of this teaching guide to learn more about how and when to implement collaborative note-taking in your classroom.

2

While there are numerous ways to assign collaborative note-taking in your course, the two most common are rotational and role based:

- Rotational Note-Taking: Assign a different student each class session to be the designated note-taker, sharing their notes with the class afterward. This ensures everyone gets the opportunity to focus on the lecture without taking notes.

- Role-Based Note-Taking: Assign specific roles and responsibilities to each member of a note-taking team to ensure comprehensive coverage of lectures or study materials. For example:

- Summarizer: One person captures and summarizes questions and answers discussed during class.

- Detailer: Another student focuses on listing key terms, relevant people, and crucial dates.

- Connector: A third individual draws connections to previous readings, discussions, or relevant external materials.

WHY?

Why is note-taking beneficial to students?

1

Research shows that note-taking leads to:

- Better academic performance: Students earn higher test scores and demonstrate better comprehension when they take notes versus not taking notes, even if they do not review their notes after recording them. (Fischer & Harris, 1973).

- Enhanced focus during class: Students who take notes are more attentive and remain engaged throughout class lectures or learning activities (Piolat, Olive, & Kellogg, 2005, Kane et al, 2017).

2

- Improved student understanding and recall of information: The process of note-taking improves student’s active listening skills, comprehension of material, encoding of information, and retention (Kiewra 1987). The process of converting information into words or images creates new neural pathways in the brain, which establishes learning concepts more robustly in our long-term memory (Brown et al, 2014, Bohay et al, 2011).

- Better review and studying skills: Effective notes cultivate efficiency by saving students time while maintaining organization and focus during study sessions. Notes also provide a great resource for creating outlines or other study tools (McPherson 2018).

Why do students struggle with note-taking?

Why do students struggle with note-taking?

Effective note-taking requires a number of skills. According to Kiewra, Colliot, and Lu (2018), students who struggle with note-taking often demonstrate deficiencies in skills key to successfully note-taking.

1

- Fine motor skills (handwriting) and/ or computer skills. Students struggle with note-taking because the speed of lectures often surpasses the speed at which they can take notes. Lectures are typically presented at a rate of 120-180 words per minute, while students average 33 words per minute typing and 22 words per minute writing longhand (Wong 2014).

- Sustained attentiveness: Several conditions can distract students and lead students to take fewer notes, such as the use of digital devices, visual aids, or audience questions (Maddox & Hoole, 1975, Kuznekoff 2022).

- Reception and processing of Information. Students often struggle to distinguish essential information from details. Quick presentation leaves little time for cognitive processing, leading to gaps in notes. Synthesizing information is challenging, making concise note translation difficult. Prior knowledge affects a student’s ability to identify key points. Language barriers or unfamiliar terms can hinder information reception.

2

- Proficiency in producing well-organized and understandable notes. Students’ notes often lack vital details, which can lead to incomplete understanding. Students are generally good at recording main ideas but tend to neglect more specific details (Kiewra & Benton, 1988). Note-taking completeness declines as ideas grow in detail and into sub-levels. In a study, students recorded 91% of top-level ideas, but this dropped to 60%, 35%, and 11% for increasingly detailed sub-levels. Crucial examples are frequently left out from notes, with a study reporting that only 13% of examples were noted (Austin et al., 2004).

- Inaccurate note-taking: Students can produce vague or incorrect notes, especially when copying numbers or diagrams ( Maddox & Hoole, 1975; Johnstone & Su, 1994).

WHY

Why Use Guided Note-taking in Your Classroom?

Guided Notes benefit students and instructors in a number of ways.

1

Students

- Improve Note-taking Skills: Guided notes nudge students toward important content, which helps ensure students produce complete and accurate lecture notes. Guided notes can bridge the gap between students with differing note-taking skills, which is especially beneficial for non-native speakers and students with learning disabilities. While tailored to support those who may struggle, guided notes are beneficial for all students, simplifying the identification of critical information during lectures.

- Promote Active Engagement: To complete guided notes, students must actively engage with lecture content through listening, observing, thinking, and writing. This enables students to more easily identify crucial information, thereby aiding comprehension and retention.

- Facilitate Classroom Interaction: Guided notes encourage students to ask more questions and make more comments during lectures (Austin et al., in press), thus creating a more interactive learning environment.

- Boost Academic Performance: Studies show that students using guided notes achieve higher test scores than those taking their own notes (Austin et al., 2022; Heward,1994; Lazarus, 1993).

- Function as Advanced Organizers: Guided notes, when reviewed prior to lectures, offer students a preview of the topics to be covered, which can enhance their understanding of the material presented.

- Relieve Anxiety: Guided notes build a sense of reassurance and confidence in students, as the guided notes reinforce which concepts have been covered in class, a video, or other instructional materials. This lessens students’ concerns that unexpected topics will appear on assessments and promotes a more predictable and consistent learning experience. (To learn more about assessments, please visit CATE’s assessment and grading practices teaching guide landing page)

2

Instructors

- Maintain Lecture Flow: Guided notes can help instructors maintain the planned flow of the lecture, ensuring it adheres to the intended content and sequence.

- Manage Lecture Content: Guided notes compel instructors to prioritize and limit their lecture content. By identifying what is truly essential for students to learn, instructors can ensure maximum student comprehension and retention.

- Streamline Exam Preparation: The content of guided notes can be easily converted into test or exam questions.

- Enhance Student Satisfaction: Students generally appreciate the effort that instructors put into preparing guided notes, often leading to positive evaluation ratings.

Why Use Collaborative Note-taking in your Classroom?

1

Studies show that collaborative note-taking:

- Produces Learning Gains: Collaborative note-taking leads to more learning gains for students than taking notes independently (Chen & Yu 2019; Harbin, 2020). This is because students interact with one another about note content more frequently when taking notes collaboratively, which may aid them in understanding the content more thoroughly.

- Reduces Cognitive Strain: Because the task of note-taking is shared among group members, the effort of attempting to write while listening is reduced for each student. This may enable students to grasp content more comprehensively (Kirschner, Sweller, Kirschner, Zambrano, & J., 2018).

- Promotes Peer Learning: Encourages students to view one another as resources, which can aid in preparing for exams and assignments.The process of revising notes with peers and adding more information has been shown to lead to the creation of higher-quality, more complete notes (Luo, Kiewra, & Samuelson, 2016).

2

- Fosters Inclusivity: Levels the playing field, especially for students with varying prior preparation.

- Enhances Classroom Engagement: Shared responsibilities lead to richer discussions and classroom participation.

- Provides students more Comprehensive Coverage: When multiple people take notes, the group is more likely to capture all the relevant information.Collaborative note-takers are likely to notice and correct incorrect or incomplete information in the notes taken by group members, thereby improving the accuracy and completeness of the notes as a whole (Kam et al., 2005).

- Offers Different Perspectives: Each note-taker may focus on different aspects or interpret information in a unique way, leading to a richer understanding of the topic.

HOW?

How to Provide Note-taking Guidance for Students

HOW?

As a university instructor, here are some strategies you can employ to help your students become better note-takers:

- Prompt early note-taking: Guide students to start note-taking as soon as the lecture begins, ensuring they don’t miss any important points.

- Promote active note-taking: Suggest students choose a seat that optimizes their ability to see and hear and urge them to remain alert during lectures.

- Promote structured note-taking: Encourage students to take notes in an organized format. This helps them identify main ideas first and then elaborate the details.

- Teach note-taking strategies: Spend some time at the beginning of the term teaching different note-taking methods and explain the benefits and drawbacks of each.

- Share examples: Discuss with students the note-taking examples outlined in this teaching guide. If possible, you could suggest a specific method most aligned with the structure of the daily lecture or course readings. You can also share your version of lecture notes after class, so that students can compare and model their notes to yours.

- Advocate for concise note-taking: Teach your students to record notes in complete thoughts while abbreviating and simplifying where possible.

- Discourage verbatim transcription: Stress the importance of understanding and summarizing content rather than attempting to create a word for word record, which can lead to missing important points. You can also suggest students use symbols to identify or emphasize items in their notes.

2

- Stress the importance of readability: Remind students to write legibly, making their notes easier to study later.

- Emphasize specialized vocabulary: Encourage students to highlight new or difficult terms and to write down or look up their definitions.

- Advocate for differentiating facts from opinions: Teach students to distinguish between factual information and the professor’s opinions, encouraging them to add their own thoughts to their notes.

- Encourage inclusion of visuals: Prompt students to copy diagrams or other visuals that aid in understanding concepts during later study sessions.

- Provide feedback: If possible, review student notes occasionally to provide feedback and suggestions for improvement.

- Encourage chronological organization of notes: Recommend students keep their notes for each class separate and start a new set each day of class. This enhances study efficiency.

- Urge consistent attendance: Impress upon students the importance of attending all lectures to ensure a comprehensive set of notes, equating it to having all of the chapters of a book.

- Stress note-taking during discussions: Advise students to take notes during tutorial discussions, allowing them to link lecture notes with tutor group discussions.

how

Specific Suggestions for Taking Notes for Videos or Audio Recordings

1

In this section, we provide specific suggestions for enhancing students’ note-taking skills when viewing videos or listening to audio recordings.

- Watch the Video Once without Taking Notes: Encourage students to watch the video once without taking notes to grasp the overall concept. This can help them understand the main ideas and details better when they watch it again for note-taking.

- Pause and Play: One of the advantages of videos is that students can pause and play the video. They should be encouraged to utilize the pause function to ensure they don’t miss any important points while taking notes.

2

- Use Video Features: If the video has closed captions or a transcript, students can use these to help with their note-taking. They can also slow down the video speed if it’s too fast for them.

- Take Screenshots: If the video has important graphics or slides, students can take screenshots for reference. These can be included in their notes as visual aids.

- Summarize: After watching each section, students should write a short summary of the key points. This will help understanding and provide a quick review source later.

- Note the Timestamp: While writing notes, students should include the video timestamp for important points. This way, they can easily revisit specific parts of the video for clarification.

How to Guide Students in Selecting the Appropriate Note-Taking Method

1

Students may be uncertain as to which note-taking method they should use. While there’s no universally perfect method, guiding students based on their preferences and learning context can lead to more effective note-taking.

- Assess the Learning Context: If the lecture follows a clear hierarchy or structure, methods like the Outline or Cornell might be more appropriate. For fast-paced lectures without a defined structure, the List Method could be beneficial. For subjects with interconnected ideas, a Concept Map can help visualize relationships. For subjects requiring comparison, the Charting Method might be ideal.

- Students’ Preferences: Students who prefer visual representations might benefit from methods like Concept Maps. Those who prefer to focus on spoken information might gravitate towards the List or Cornell Method, where they can jot down what they hear and then review and restructure their notes later. Students who prefer to actively engage with the material might find methods like the Cornell Method or drawing out Concept Maps more effective.

2

- Practice and Refinement: Encourage students to experiment with multiple methods. After several sessions, they can reflect on which method facilitated better understanding and recall.

- Combine Methods: Students shouldn’t feel restricted to one method, either during initial note-taking sessions or when reviewing notes later. Combining techniques, like starting with the List Method and then restructuring into an Outline, can be beneficial.

- Regular Reviews: Periodically discuss note-taking techniques with students. Encourage feedback on what’s working for them and what isn’t, which fosters refinement of their methods.

- Provide Templates and Examples: Offer students the templates provided here for each method, as they can guide and simplify the note-taking process. With a structure in place, they can focus more on content.

How to Develop Lectures that Promote Effective Note-taking

How to Develop Lectures that Promote Effective Note-taking

1

Implementing the following techniques in your classroom works to improve student note-taking:

- Provide a preview: At the beginning of the lecture, provide an overview of what you’ll be covering.

- Structure the presentation: Break your lecture into clear, digestible sections. Introduce each section with its key points or objectives. Conclude each section by summarizing or restating these points. This structured approach not only helps students focus on the most important information, but also gives them cues for when to start and stop taking notes.

- Incorporate verbal and visual cues into the lecture: Enhance the structure of your lecture through verbal cues like phrases indicating relationships (e.g., “The main arguments are…”, “A major development was…”) or highlighting key points. Visual cues can include using the board or slides to highlight specific concepts, presenting graphs or complex charts, or sharing a running outline of the lecture. These cues help students discern the structure of the lecture and make it easier for students to organize their notes.

- Pace the lecture: Try to aim for an ideal pace of approximately 135 words per minute. This pace has been documented as the optimal speed for comprehension and note-taking (Peters, 1972). However, the nature of the material should also influence the pace. Complex, unfamiliar, or technical content requires slower delivery to aid student comprehension and recording. A faster paced lecture might be suitable for more familiar or narrative-driven lecture material.

- Utilize strategic pauses: Build short, regular pauses into your lecture to give students time to write. These pauses can be after you introduce a new concept, finish a section, or make a particularly important point. This helps ensure that students can keep up with the pace of the lecture and accurately record the information.Researchers have found that pausing for just 2-3 minutes during a lecture and giving students time to review their notes can significantly increase short term memory and get that information into students’ long term memory (Prince, 2004).

2

- Incorporate note-taking activities into class sessions: If you continue talking at your students for an extended period of time just to cover the material, you’re not offering students the opportunity for reflection and engagement. Instead, try these techniques:

- Note review: Reviewing notes and discussing them with peers provides students with the opportunity to review and rework their notes, thereby solidifying their understanding of the lecture material

- Interactive learning: Ask questions and engage in discussions during the lecture. This helps maintain engagement and encourages students to consider the information more deeply. This can also give you an opportunity to clarify or elaborate on points that students find difficult.

- Prediction activity: Ask students to write three possible answers to a question that will be answered in the next section of the lecture. Share the question, give students time to think and write down their answers, and then proceed with the portion of the lecture pertaining to these questions.

- Free recall exercise: Conclude your lecture with a few minutes for a “free recall” exercise to improve retention. For example, ask students to write down everything they can remember from the lecture, which promotes memory reinforcement (Bonwell & Eison, 1991; Ruhl et al., 1987; Prince, 2004).

- Session recap: At the end of the lecture, summarize the main points. This helps students prepare for what is to come, structure their notes effectively, and reinforce the material.

NOTE: All of the techniques described above also apply to creating effective videos. To learn more about creating videos, consult CATE’s teaching guide: Micro-lecture Videos

How to Reduce the Need for Accommodation Requests via Active Note-taking Support

How to Reduce the Need for Accommodation Requests via Active Note-taking Support

1

Note-taking accommodations are among the most common support services requested by students. Students with a variety of disabilities – including ADHD, dyslexia, auditory processing issues, visual or hearing impairments or other physical disabilities – are eligible for note-taking accommodations. Accommodations are needed when a student’s disability impacts their ability to interpret the lecturer’s audio or visual presentation, maintain focus during in-class instruction, or write or type notes. The Disability Resource Center offers the following support for students in need of note-taking accommodations:

- Lecture Recording: The student requesting the accommodation may record lectures using a digital recorder or other assistive technology or software.

- Instructor Lecture Notes: A student requesting this accommodation is provided the instructor’s lecture notes prior to the session.

- Peer Note Taker: A classmate assigned by DRC shares their class notes with the student requesting the accommodation. To initiate this accommodation, students should submit a peer note taker request form.

While note-taking accommodations are a necessity for some students, there may be some students who seek accommodations because they have not learned successful note-taking strategies or feel insecure about their note-taking abilities. Instructors can implement several strategies to minimize the need for note-taking accommodations, improve all students’ note-taking abilities, and build a more inclusive classroom environment.

Note: The effectiveness of these strategies can depend on the needs of the students in your classroom, and they should be seen as part of a comprehensive approach to support that may also include accommodations.

2

An approach to reducing the need for individual note-taking accommodations is to proactively provide similar support to all students in your course. This can include:

Sharing lecture materials before or after class: Sharing lecture notes or slide decks prior to a session can be beneficial to students who struggle with taking notes. It can be helpful to refer to these notes during the lecture, and having access to these materials before the session allows students to review the material and come to class prepared to engage more deeply with the content. You may post these materials digitally via Blackboard, or you opt to hand out these materials in class with space for students to add additional notes. If you prefer students to create their own notes before accessing your lecture materials, make sure to post course materials on Blackboard after the session.

Sharing audio or video lecture recordings: Sharing audio or video lecture recordings to your Blackboard course site is an effective method of decreasing the need for note-taking accommodations. Lecture recordings can provide adaptable, highly flexible, and convenient access to learning materials (Nkomo and Daniel 2021). By providing all students with the option to revisit lectures at their own pace, students are better able to absorb complex concepts, catch details they may have initially missed, and take more comprehensive notes.

Using guided note-taking strategies: Guided note-taking offers a consistent, structured outline that aids all students in concentrating on essential information, arranging their ideas, while also encouraging active participation by having students complete key concepts and summaries during lessons to enhance comprehension and retention.

Using collaborative note-taking strategies: Collaborative note-taking shares the note-capturing load among students, easing the demand on those with attention or writing difficulties; this can diminish the need for individual accommodations. Exposure to peers’ varied note-organizing methods boosts comprehension and can lessen reliance on personalized support.

How to Incorporate Inclusive Note-taking Strategies in Your Classroom

How to Incorporate Inclusive Note-taking Strategies in Your Classroom

1

Clear, concise notes enable students to prepare for class sessions, optimize their study time, and demonstrate their knowledge in assessments. However, effective note-taking can pose a challenge for students.

2

To ensure all students have thorough and comprehensive course notes, instructors can implement proactive, inclusive-centered note-taking strategies through guided and collaborative note-taking.

How to Choose between Guided Note-taking and Collaborative Note-taking

How to Choose between Guided Note-taking and Collaborative Note-taking

1

Guided notes are handouts that outline the lecture content with blanks for key concepts, facts, or relationships that students fill in during the lecture. Collaborative note-taking is a pedagogical strategy where students take notes on the same material and then share, compare, and consolidate their notes. Guided and collaborative note-taking offer distinct advantages, but choosing between them (or combining them) requires an understanding of the learning objectives and the classroom environment. Here are some factors to consider before implementing these note-taking strategies.

Learning Objectives and Content Structure:

- Guided Note-taking: If the objective is to ensure students grasp key concepts and don’t get overwhelmed by the volume of information, guided notes can be beneficial. They are especially useful for complex subjects where the educator wants to highlight specific points.

- Collaborative Note-taking: If the objective is to foster an environment of collective learning, sharing, and knowledge dissemination, then collaborative note-taking is the best strategy. It is especially beneficial for subjects that encourage group activities, discussions, and peer-to-peer interactions.

2

Class Size:

- Guided Note-taking: Larger classes, where individual attention is challenging, can benefit from guided notes as they provide a structured path for all students to follow.

- Collaborative Note-taking: In smaller classes or discussion groups, collaborative note-taking can be more easily managed and can encourage active participation from all students.

Student’s Prior Knowledge:

- Guided Note-taking: For beginners or those unfamiliar with a subject, guided notes can provide a roadmap, helping them focus on essential details.

- Collaborative Note-taking: More advanced students can benefit from the diverse perspectives and insights that emerge from collaborative note-taking.

Combining Guided and Collaborative Note-taking

Combining Guided and Collaborative Note-taking

1

You may also choose to integrate collaborative and guided note-taking methods in a single lecture and discussion session. Begin the session by distributing guided notes to ensure all students grasp the foundational knowledge. As the lecture or discussion progresses, these notes serve as a structured starting point. Post-lecture/discussion, encourage students to form groups to discuss, compare, and expand upon these notes collaboratively.

2

This integrated approach ensures that while students benefit from structured guidance, they also engage in peer discussions, benefiting from diverse insights and perspectives, which further enhances their understanding and retention of the material.

How to

How to Create Guided Notes

1

Creating guided notes can be an effective tool in promoting active learning and retention among students. Though the process of creating guided notes might seem straightforward, achieving the right balance between providing guidance and promoting active note-taking does take some planning and preparation. Here are steps to getting started in crafting effective guided notes:

- Determine Core Concepts and Themes:

- Before creating your notes, identify the primary ideas and themes intended for the particular class or lecture.

- This ensures you remain centered on the core concepts aspects of the lesson.

- Align with Course Learning Objectives:

- All notes should serve a purpose beyond just being a lecture summary.

- Aim to align your guided notes with the learning objectives of the course. This ensures that the notes guide students towards achieving specific learning milestones. To learn more about craft effective learning objectives, consult CATE’s teaching guide: Learning Objectives

- Regularly revisit the course’s learning objectives and cross-check with your notes to maintain this alignment.

2

- Structure the Content:

- Organize your content thoughtfully. This involves creating a structured outline that makes use of headers and subheaders, allowing for a logical flow of information.

- By breaking down complex topics into digestible segments, you facilitate ease of understanding and better retention.

- Incorporate interactive elements like prompts or reflective questions throughout the notes. This nudges students to grapple actively with the content, promoting deeper comprehension and critical thinking.

- Keep it Simple:

- Ensure your notes are concise, prioritizing clarity over complexity. This doesn’t mean omitting important details, but rather presenting them in a way that is’s straightforward and digestible.

- Be mindful of cognitive overload. Bombarding students with too much information can be counterproductive. Instead, focus on delivering the essentials in a clear format.

- Ask for Student Feedback:

- Encourage students to provide feedback on the guided notes. Understanding what works and what doesn’t from a student’s perspective can offer insights for future revisions.

- Continuous iteration based on feedback ensures your guided notes evolve in line with student needs.

Tips for Implementing Guided Notes Effectively in Your Classroom

1

- Incorporate Visual Aids: Enhance your guided notes by integrating visual elements like maps, diagrams, charts, and graphs. Visual aids are a great way to enhance student comprehension of complex concepts and resonate well with learners who like to learn visually. Rather than burdening students with drawing complex figures in their notebooks or recreating them digitally, consider supplying a basic graphic in the guided notes. Spaces can be left blank for students to annotate further. For example, provide a partially complete diagram and ask students to label specific components or provide a graph for students to label axes or plot curves.

- Facilitate Conceptual Connections: Introduce concept maps, another type of guided notes, to help students to organize information and make connections between different concepts. You can supply a concept map or ask students to create their own during lectures. This approach is particularly advantageous for students who find linear note-taking challenging and gravitate towards a graphical format.

- Multimedia Assignments: Pair guided notes with readings, podcasts, or video assignments. When students are presented with content across multiple modes, guided notes can help direct attention to key concepts and ideas. Especially for lengthier assignments, guided notes can help students chunk the content more effectively.

2

- Use Generative AI to Create Guided Notes: You can input lecture notes or other instructional materials into ChatGPT or another Generative AI tool to create a draft of your guided notes. See the CATE’s teaching guide AI Writing Tools for more information.

- Student-generated Guided Notes: Engage your students actively by designating groups to create guided notes for specific content segments, be it a section, topic, or chapter. Encourage peer teaching by asking each group to teach or present their designated content to the class.

- Pair/ Share Activity: Intersperse your lectures with scheduled breaks for pair/share activities. Direct students to collaborate with a peer, exchanging insights from their guided notes. This time can serve as a platform for students to fill in any gaps in understanding, address areas of confusion or concern, or dig deeper into topics.

- Collaborative Note-taking: Assign groups to create guided notes for a chunk of content. This strategy gets your students involved in the process of creating guided notes. Assign each group to a chunk, section, or chapter to outline for their peers. You could even take it a step further by asking each group to teach or present their assigned chunk of content.The next section of this guide describes collaborative note-taking in greater detail

How to Implement Collaborative Note-taking in Your Classroom

1

- Adopt a Predictable Lecture Format: Recurring slides like “What’s Coming Next,” “What We’re Doing Today,” and “Question to Consider” can guide student note-taking. This structured format bridges gaps from varied note-taking quality and levels of student preparation.

- Encourage Explicit Discussions: Facilitate conversations where students can set expectations and norms for the collaborative document. This might include taking verbatim vs. paraphrased notes, using color codes to distinguish information, and managing differing note-taking expectations.

- Be Clear on the Role of Notes: Emphasize that collaborative notes are a supplementary resource, complementing personal engagement with course materials, and not an authoritative study guide.

2

- Use a Pre-class Survey: To assess interests and preparation levels and strategically pair students. This helps in understanding and aligning varied note-taking quality.

- Allocate Time for Peer Review: After individual note-taking, allocate time for students to swap notes and add additional insights, ensuring thorough coverage and varied perspectives.

- Monitor Group Dynamics: Stay vigilant of group dynamics affecting the note-taking process and foster an environment where students can communicate concerns openly (Harbin 2020).

Collaborative Note-taking Tools

1

Below are various collaborative note-taking techniques suitable for the UIC classroom. Make sure that the tool selected is accessible and comfortable for all students participating in collaborative note-taking.

- Shared Online Documents: Create a shared Google Doc where all students can contribute and edit notes simultaneously. Alternatively, Microsoft features shared documents or notebooks, where students can access and add information collectively.

- Wiki Platforms: Develop a class wiki where students can add, modify, and organize notes, fostering a collaborative digital environment. Blackboard offers a wiki platform.

- Collaborative Annotation Tools: Use tools like Hypothes.is or Perusall for annotating web pages and PDFs collaboratively, facilitating dialogue within the text.

2

- Mind Mapping: Use mind mapping tools like MindMeister or Miro where students can collaboratively create visual notes, linking concepts in a visually appealing and structured manner.

- Collaborative Boards: Use digital boards like Padlet where students can post notes, images, links, and documents, allowing for real-time collaboration and sharing.

- Cloud Storage: Use cloud storage platforms like Google Drive, OneDrive, or Box to create shared folders where all notes and relevant documents are stored, accessible to all participants.

- Audio/Video Sharing: Share audio or video recordings of notes or brief summarizing podcasts that can be accessed by peers asynchronously.

HOW TO USE/CITE THIS GUIDE

- This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International.

- This license requires that reusers give credit to the creator. It allows reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, for noncommercial purposes only.

Please use the following citation to cite this guide:

Stapleton-Corcoran, Erin (2023). “Note-taking.” Center for the Advancement of Teaching Excellence at the University of Illinois Chicago.

REFERENCES

References

Austin, J. L., Lee, M., & Carr, J. P. (2004). The effects of guided notes on undergraduate students’ recording of lecture content. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 31, 314–320

Austin, J.L., Lee, M.G., Thibeault, M.D. et al. (2022) Effects of Guided Notes on University Students’ Responding and Recall of Information. Journal of Behavioral Education 11, 243–254. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021110922552

Bohay, M., Blakely, D. P., Tamplin, A. K., & Radvansky, G. A. (2011). Note Taking, Review, Memory, and Comprehension. The American Journal of Psychology, 124(1), 63–73. https://doi.org/10.5406/amerjpsyc.124.1.0063

Bonwell, C. C., & Eison, J. A. (1991). Active learning: Creating excitement in the classroom. Washington, D.C.: George Washington University.

Brown, P. C., Roediger, H. L., & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Make it stick: the science of successful learning. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674419377

Chen, P.-H., Teo, T., & Zhou, M. (2017). Effects of Guided Notes on Enhancing College Students’ Lecture Note-Taking Quality and Learning Performance. Current Psychology (New Brunswick, N.J.), 36(4), 719–732.

Chen, W., & Yu, S. (2019). Implementing collaborative writing in teacher-centered classroom contexts: student beliefs and perceptions. Language Awareness, 28(4), 247–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2019.1675680

Fisher, J. L., & Harris, M. B. (1973). Effect of note taking and review on recall. Journal of Educational Psychology, 65(3), 321–325.

Harbin, M.B. (2020). Collaborative note-taking: a tool for creating a more inclusive college classroom. College Teaching, 68 (4).

Heward, W. L. (1994). Three “low-tech” strategies for increasing the frequency of active student response during group instruction. In R. Gardner III, D. M. Sainato, J. O. Cooper, T. E. Heron, W.L. Heward, J. W. Eshleman, & T. A. Grossi (Eds.), Behavior analysis in education: Focus on measurably superior instruction (pp. 283–320). Belmont, CA: Thomson Brooks/Cole Publishing Co.

Kiewra, K. A. (1987). Notetaking and review: The research and its implications. Instructional Science, 16, 233-249.

Kiewra, K. A., & Benton, S. L. (1988). The relationship between information-processing ability and notetaking. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 13(1), 33–44.

Kiewra, K. A., Colliot, T., & Lu, J. (2018). Note This: How to Improve Student Note Taking. (Vol. 73, Ser. Idea Paper, pp. 1–18). New York, NY: IDEA Center, Inc.

Kirschner, P. A., Sweller, J., Kirschner, F., & Zambrano R., J. (2018). From cognitive load theory to collaborative cognitive load theory. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 13(2), 213–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-018-9277-y

Kobayashi, K. (2006). Conditional effects of interventions in note-taking procedures on learning: A meta-analysis. Japanese Psychological Research, 48(2), 109–114.

Kuznekoff, J. H. “Digital Distractions, Note-Taking, and Student Learning.” Digital Distractions in the College Classroom, edited by Abraham Edward Flanigan and Jackie HeeYoung Kim, IGI Global, 2022, pp. 143-160. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-9243-4.ch007

Lazarus, B. D. (1993) Guided notes: Effects with secondary and post secondary students with mild disabilities. Education and Treatment of Children, 16, 272-289.

Maddox, H., & Hoole, E. (1975). Performance decrement in the lecture. Educational Review, 28(1), 17–30.

McPherson, F. M. (2018). Effective notetaking (3rd ed.). Wayz Press.

Nkomo, L. M., & Daniel, B. K. (2021). Providing students with flexible and adaptive learning opportunities using lecture recordings. Journal of Open, Flexible, and Distance Learning, 25(1), 22–31.

Pauk, W.; Owens, Ross J. Q. (2010). How to Study in College (10 ed.). Boston, MA: Wadsworth.

Peters, D. L. (1972). Effects of note taking and rate of presentation on short-term objective test performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 63(3), 276–280. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0032647

Piolat, A., Olive, T., & Kellogg, R. T. (2005). Cognitive Effort during Note Taking. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 19(3), 291–312.

Prince, M. (2004). Does Active Learning Work? A Review of the Research. Journal of Engineering Education (Washington, D.C.), 93(3), 223–231. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2168-9830.2004.tb00809.x

Ruhl, K.L., Hughes, C.A., & Schloss, P.J. (1987). Using the pause procedure to enhance lecture recall. Teacher Education and Special Education, 10, 14-18.

Suritsky, S. K., & Hughes, C. A. (1991). Benefits of notetaking: Implications for secondary and postsecondary students with learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 14, 7–18. https://doi.org/10.2307/1510370

Wong, L. (2014). Essential study skills (8th ed.). Stamford, CT: Cengage Learning.