Pronoun Usage

Introduction

Jackson Bartlett, Associate Director for Inclusive Teaching at CATE

August 8, 2022

intro

column 1

The menu of personal pronouns in the English language continues to expand to better reflect the gender diversity within our society.

Moving beyond the him/her binary, trans, nonbinary, and gender expansive communities in particular have advocated for 1) the use of gender neutral pronouns like they/them and neopronouns (new pronouns) such as ze/zir; and 2) the voluntary sharing of pronouns to avoid relying on assumptions about gender identity when interacting with others. This guide offers basic guidance for pronoun usage and provides tools instructors can use to build inclusive classrooms that are more gender-affirming for all.

column 2

Everyone has pronouns, regardless of gender identity.

WHAT

Gender Identity & Pronouns

column 1

Personal pronouns are the words we use to refer to one another in multiple tenses without using proper names (she/her/hers, for instance). In English and in many other languages, pronouns are gendered. In these languages, gender is the only direct information pronouns contain. They’re also binary, assuming that there are only two genders: male and female. In languages with gendered pronouns, pronoun usage centers binary gender identity in conversation, in writing, and in our thought processes about ourselves and one another (Prewitt-Freilino, Caswell, & Laakso 2012). The University Library provides an overview of the history of pronouns here.

column 2

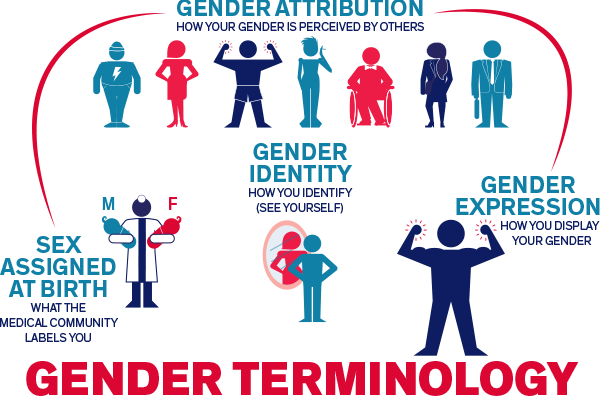

Pronouns thus have a lot to do with gender identity. But what is gender identity? Gender identity can come from sex assigned at birth and inferences by others based on assumptions about what a certain gender should look or act like. This is known as gender attribution. Importantly, however, gender identity is also based on gender expression, or how one personally identifies and wishes to display their gender to others.

Some people identify with a gender other than that which was assigned at birth. In this case, they may wish to use pronouns for the other gender in the binary. For example, if someone’s assigned gender was male but they identify as female, they would go from using he/him pronouns to she/her.

column 3

Adapted from the Gay, Lesbian, and Straight Education Network’s Gender Terminology Guide

column 4

Additionally, though, trans, nonbinary, and gender expansive communities have advocated for a more expansive menu of pronouns to better reflect the range of gender identities or to reject the gender binary altogether. This has led to the introduction of gender neutral pronouns such the singular “they/them/theirs” and neopronouns (new pronouns) like “ze/zir/zirs,” for example, and gender neutral honorifics (Mr./Mrs.) such as “Mx.”

In either case, it’s important when referring to others to use the pronouns the other person identifies with rather than the pronouns we may assume are appropriate based on visual or other cues.

column 5

Beyond personal pronouns there are other types of language interventions to neutralize the gender binary. “Latinx” or “Latiné,” for instance, instead of Latino and Latina, which denote male or female with the “o” and the “a.”

———————————————————————————

As awareness of gender identities beyond the binary of male/female grows, pronouns and pronoun usage have adapted to reflect this understanding. →

column 6

Some commonly used pronouns

WHY

Matching Gender Attribution & Gender Identity

column 1

Gender attribution and gender expression are not always aligned when it comes to pronoun usage. Pronouns are often assumed and those assumptions may fail to reflect a person’s actual gender identity and gender expression.

The research is clear that those experiencing a mismatch between gender attribution and gender expression (also known as misgendering) are more likely to experience depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, and other negative mental health outcomes (Becerra-Culqui, Liu, & Nash 2018; Ehlinger, Folger, & Cronce 2021; Kapusta 2016; Mclemore 2015). By contrast, the use of names and pronouns that accurately reflect gender identity decreases those negative outcomes (Russell, Pollitt, Li, & Grossman 2018; Vance 2018). Researchers have found that misgendering is one of the more salient negative experiences of trans and non-binary students in higher education.

Misgendering can not only cause distress, but it can send messages about misgendering as an acceptable practice in the fields students plan to enter (Whitley 2022).

column 2

Accurate gender attribution, on the other hand, can send positive messages about inclusion and classroom and campus climate (Goldberg, Beemyn, & Smith 2018; Goldberg & Kuvalanka 2019; Marine & Nicolazzo 2014; McKinney 2005; Nicolazzo 2016; Prior 2015; Seelman 2014; Stolzenberg 2017).

Misgendering is so impactful for our students because it’s tied to broader patterns of discrimination in society and to the disproportionate violence and family exclusion trans and gender nonconforming people face. What may seem like just a personal slight to a a cisgendered person (a person whose sense of personal identity and gender corresponds with their birth sex) may signal danger to someone whose gender identity could make them the target of violence outside the classroom.

As we seek to create inclusive classroom spaces where students feel seen, heard, and ready to learn, it’s important to use the pronouns that accurately reflect a student’s gender identity. But if we’re not supposed to assume someone’s gender, how do you get it right?

HOW

Using Pronouns Effectively

column 1

As instructors, there are things we can do to create gender-inclusive spaces in our classrooms. The first is to create space for students to safely express their gender identities in the learning environment. When those in the learning community feel confident sharing pronouns, instructors and students have the information they need to respect the gender identity of others. The second is to signal gender-inclusive values to students and establish effective community guidelines for respectful and healthy communication across social differences. Students do not tend to enter spaces assuming they are inclusive; rather, they look for cues. Lastly, as instructors we can practice strategies for managing misgendering when it does occur in ways that promote growth for ourselves and our students.

column 2

NOTE: As with many inclusive teaching practices, creating gender inclusive learning environments is an ongoing practice. Things that may be new for a given instructor, like using neopronouns or asking for pronouns, will become easier over time. And as social norms around gender identity continue to evolve, what gender inclusivity looks like may also evolve.

HOW continued

Making Space for Gender Difference & Gender Expression

The classroom is not just a place where students learn content. It’s a social space, full of interactions, language, signals, and affect. Being intentional about the social aspects of the space will help students not just have a positive experience, but also learn better.

column 1

- Instructor role: The role of the instructor is to support student’s educational and personal development. For our students, identity exploration can be a big part of that development (Patton 2016). Leaning into the complexity of identity and seeing it as a normal part of student development can go a long way toward creating welcoming and inclusive spaces for students regardless of their gender identity.

- Sharing pronouns: Invite students to share pronouns as they introduce themselves, and to restate name and pronouns when they share out in discussion later on. NOTE: Inviting students to share if desired rather than requiring them to share removes the pressure for students to out themselves if they’re not comfortable sharing pronouns or discussing gender identity in the learning space.

column 2

- Knowing our students: Whether in a large introductory level class or a graduate seminar, there are ways to get to know our students and avoid misgendering them.

- Show your students how to update their preferred names and personal pronouns in Banner and on Zoom. You can also ask students what they’d prefer to be called and make a note on your roster.

- Consider sending out an intake survey where you ask students questions about their lives, and if there’s anything they’d like you to know.

- Spend time on introductions and get-to-know-you activities early in the semester. For large classes, consider asking students to make an identity slide where they’re free to share things they’d like you and their classmates to know.

- Make use of engaged teaching strategies to interact more with your students and foster interaction between students.

- Make it known that pronouns can change, and that students are welcome to update you as needed.

Inclusive Language

Inclusive language requires both knowledge and practice. Things that might seem perfectly natural to you may not be perceived as inclusive by students or colleagues. Over time, new language and habits become more natural:

column 1

- Use gender-neutral language: The English language (and many others) reinforce the gender binary. Phrases like “ladies and gentleman” or “you guys,” in addition to binary pronoun usage, can be limiting when we’re trying to create a gender-inclusive classroom. Consider saying “you all” or “y’all” instead of “you guys,” or making more use of they/them in the singular to avoid misattribution. In the Spanish language, the use of x or e instead of o/a is a helpful tool (Latinx and Latine instead of Latino/Latina for instance). See this guide from UNC Chapel Hill for more examples of gender neutral language.

- Avoid otherizing language: Some language may signal an unfamilarity with or lack of acceptance of LGBTQ+ and gender nonconforming students. This includes words like “lifestyle” which indicates that student’s identities are deviant choices, or the phrase “preferred pronouns”, which suggests accurate pronoun attribution is up to the discretion of the user. It’s also important when referring to students’ genders not to apply the phrase “identifies as” only to trans or gender nonconforming students, while referring to cis students simply as male or female, woman or man. You can simply refer to the gender identity of the student without the qualifier. For more discussion on inclusive language, see this media guide from GLAAD.

column 2

- Don’t Deadname: Just as it’s important for instructors to match gender attribution to gender expression in the use of pronouns, it’s important to use the names your students wish to go by as well (this goes for all students, not just those who identify as trans or gender nonconforming). For trans students specifically, “deadnaming” is a practice whereby people are addressed by their previous name, not the name they go by in the present. It’s a form of misgendering and can be very disruptive for the student and disrespectful. To avoid deadnaming, ask all students to share how they would like to be addressed in the beginning of your course, and make a note in the roster. Students can add their preferred names or nicknames as well as phonetic pronunciation. Encourage students to update their names on Zoom, and in Banner (as noted above).

Signaling Inclusion & Establishing Shared Norms

Instructors send messages all the time about what we value, whether we know it or not. Fortunately, there are many ways to signal inclusion to our students. When it comes to gender identity and pronouns, we can:

column 1

- Signal & Model: Share your own pronouns when you introduce yourself, and include them in your syllabus and email signature. This sends the message that pronoun sharing is customary and welcome (and remember, not required) in your classroom. You’re also modeling for students when you ask for pronouns, use pronouns accurately, and respond appropriately when you make a mistake (see below). For some instructors, it might make sense to put a rainbow sticker on your door, or adopt the rainbow theme on Zoom. Whatever it is, do what works for you as an instructor!

- Frame it: As with any inclusive teaching practice, it goes further when you’re transparent about the why. Be frank with students about your values and practices. Why does honoring gender diversity matter? Why is it important to respect gender identity?

column 2

- Establish shared norms: It’s one thing to create a list of rules in your syllabus to signal inclusion (i.e. “in this class, we will respect one another’s pronouns”). It can go even further, however, to create norms together as a class. What’s important to students? What can they expect of themselves, and of each other? What can they expect from you? Co-constructing norms and community guidelines can help students take ownership over the space and their actions, and they’re things the learning community can refer back to when members deviate from expectations.

Managing Mistakes & Fostering Growth

Everyone makes mistakes. It’s important that, as instructors, we are vulnerable enough with our students to move forward from those mistakes in healthy and productive ways, which have the wellbeing of your students and the learning community at heart:

column 1

- Embrace a growth mindset: As instructors, we sometimes feel like we have to “get it right” all the time, and that if we mess up, our authority or credibility are undermined. Vulnerability is a key ingredient to trust, and trust helps us navigate mistakes in learning communities.

- Own mistakes: The most important thing when we misgender someone is to self-correct if we catch ourselves and be willing to be corrected when we don’t. It may be uncomfortable, but it is not something from which we cannot recover. Following up with students in real time and/or soon after the fact can go a long way toward repairing harm, and can serve as a good example to set for students who may not know how to respond when they misgender someone. NOTE: It’s important to keep this student-centered and not make it about your own sense of guilt or shame as the instructor. That places pressure on the student to tend to your needs instead of theirs.

column 2

- Have a plan: Misgendering can be considered a microaggression: a denigrating and potentially hurtful message, either intentional or unintentional, about a person’s group membership. When microaggressions occur around gender identity and in general, it’s important to have a plan for how to respond. See this article from Faculty Focus on how to respond to microaggressions.

HOW TO USE/CITE THIS GUIDE

- This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International.

- This license requires that reusers give credit to the creator. It allows reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, for noncommercial purposes only.

Please use the following citation to cite this guide:

Bartlett, Jackson Christopher (2022). “Pronoun Usage.” Center for the Advancement of Teaching Excellence at the University of Illinois Chicago. Retrieved [today’s date] from https://teaching.uic.edu/resources/teaching-guides/inclusive-equity-minded-teaching-practices/pronoun-usage/

RESOURCES, REFERENCES & CITING THIS GUIDE

RESOURCES

COLUMN 1

Guide to Gender Inclusive Language, University of North Carolina Chapel Hill

Media Reference Guide, The Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation

Souza, Tasha (2018). “Responding to Microaggressions,” Faculty Focus.

The Gender & Sexuality Resource Center

The GSC is a place on campus where students, faculty, and staff can go for programs, interactive workshops, special events, and support for issues related to gender and sexual identity.

Trans Resource Guide

This guide provides information on social and medical transitioning, legal services, education, community and wellness, and housing for trans students, faculty and staff at UIC.

History of Pronouns

UIC Library Resources on the history of gendered and nonbinary pronouns.

column 2

The Brave Space Alliance

The BSA calls itself the first Black-led, trans-led LGBTQ+ Center in Chicago. Located on the South Side, it has a community pantry and provides programming and support for housing, healthcare, employment, and community organizing.

The Center on Halsted

The CoH is an LGBTQ+ community center that provides services and programming for the region’s LGBTQ+ communities. They also provide rapid HIV testing, social programming, vocational training, and support for small community organizations.

Howard Brown Health

Howard Brown provides healthcare services for all, including expert physical and mental healthcare for LGBTQ+ communities with multiple Chicago locations. They have a sliding scale for the cost of services they provide.

Affinity Community Services

ACS is a Black-led, queer led organization on Chicago’s south side dedicated to social justice in Chicago’s Black LGBTQ+ communities.

REFERENCES

column 1

Ehlinger, P., Folger, A., & Cronce, J. M. 2021. “A qualitative analysis of transgender and gender nonconforming college student’s experiences of gender-based discrimination and intersections with alcohol use. Psychology of Addictive behaviors.

Goldberg, A. E., Beemyn G, & Smith, J. (2018). “What is needed, what is valued: Trans students’ perspectives on trans-inclusive policies and practices in Higher Education.” Journal of Educational & Psychological Consultation 29(1), pp. 27-67.

Goldberg, A. E., Kuvalanka, K., & Dickey, l. (2019). Transgender graduate students’ experiences in higher education: A mixed-methods exploratory study. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 12(1), 38–51.

Kapusta, Stephanie. 2016. “Misgendering and its Moral Contestability.” Hypatia 31(3): 512-519.

Marine, S. B., & Nicolazzo, Z. (2014). Names that matter: Exploring the tensions of campus LGBTQ centers and trans* inclusion. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 7, 265–281.

McKinney, J. S. (2005). On the margins: A study of the experiences of transgender college students. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Issues in Education, 3, 63–75.

McLemore, K. A. (2015). Experiences with misgendering: Identity misclassification of transgender spectrum individuals. Self and Identity, 14, 51–74.

column 2

Nicolazzo, Z. (2016). Trans in college: Transgender students’ strategies for navigating campus life and the institutional politics of inclusion. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Patton, L. (2016). Student development in college: Theory, Research, & Practice (3rd Edition). Jossey-Bass.

Prewiit, Freilino, Jennifer L., T. Andrew Caswell, and Emmi K. Laakso. 2012. “The gendering of language: A comparison of gender equality in countries with gendered, natural gender, and genderless languages.” Sex Roles 66(¾): 268-81.

Pryor, J. (2015). Out in the classroom: Transgender student experiences at a large public university. Journal of College Student Development, 56, 440–455.

Seelman, Kristie L. 2014. “Recommendations of transgender students, staff, and faculty in the USA for improving college campuses.” Gender and Education 26(6): 618-35.

Stolzenberg, E. B., & Hughes, B. (2017). The experiences of incoming transgender college students: New data on gender identity. Liberal Education, 103(2), 38–43. Weinberg, Michael. 2009. “LGBT-inclusive Language.” The English Journal 98(4): 50-51.

Whitley, Cameron T. 2022. “I’ve Been Misgendered So Many Times: Comparing the experiences of chronic misgendering among transgender graduate students in the social and natural sciences.” Sociological Inquiry